RAILWAY BLUE PLAQUES: ILLUSTRATING 200 YEARS OF THE RAILWAYS

To celebrate two centuries of passenger railways accidental historian Danny Coope of Street of Blue Plaques has been commissioned by Southeast Communities Rail Partnership to create 200 plaques across ten South East lines for RAILWAY200’s nationwide events.

DANNY’S RAILWAY200 BLUE PLAQUES ON DISPLAY AT LEWES TOWN HALL, 1 AUGUST 2025

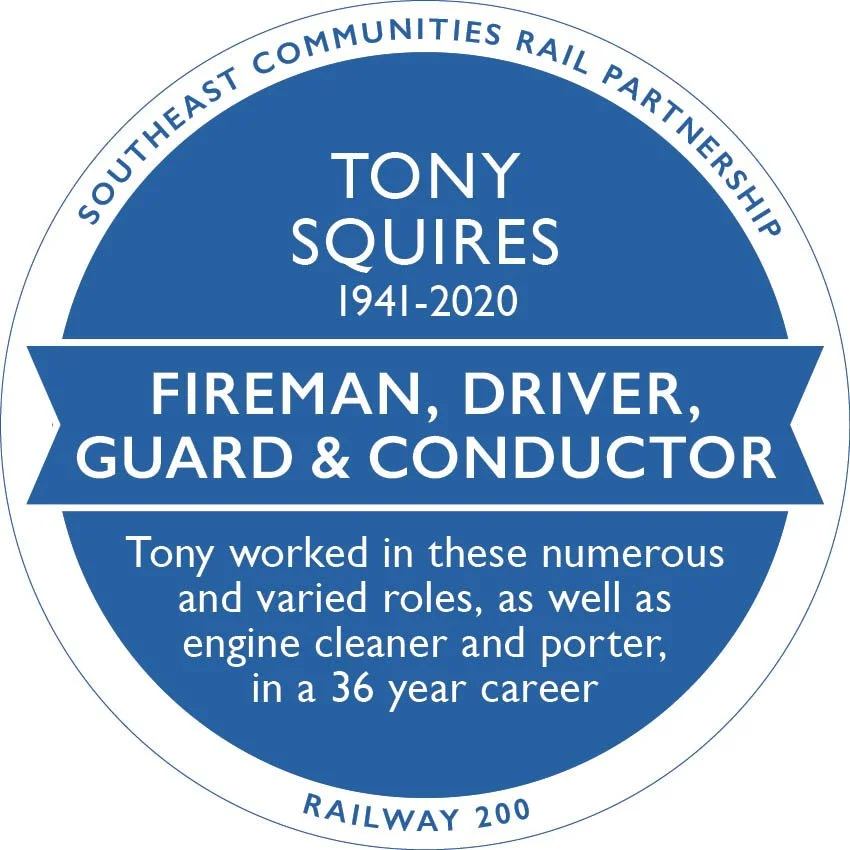

A really broad spectrum of people are being remembered, through whose lives and occupations we’re able to illustrate 200 years of railway history: People who’ve either made a contribution to the building of the railways, the running of the railways, making use of the railways or having their life influenced or enhanced by the railways.

There are 100 historical plaques with fascinating backstories, mostly researched and written by Danny himself, based on his own discoveries and nominations from Community Rail Line Officers and local history groups.

Danny occasionally exceeded the fair-use terms on the Findmypast website by clicking too efficiently through hundreds of census records and newspapers online. For a few intense hours he became an expert in milk trains, railway navvy riots, WH Smiths and King Louis Philippe of France, but was soon down another rabbit hole.

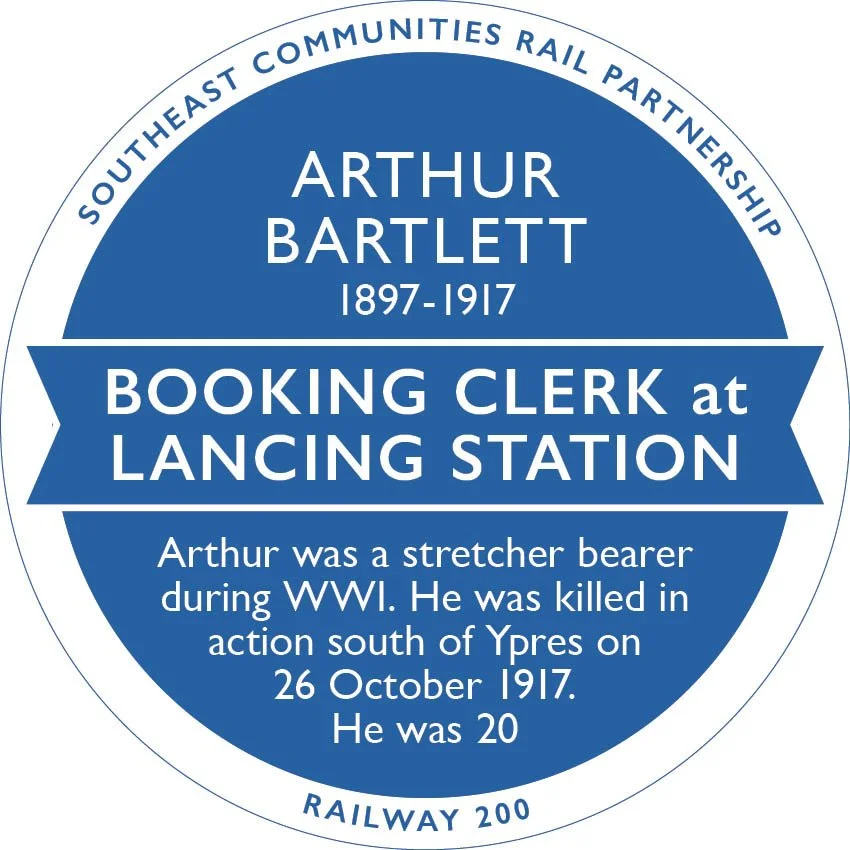

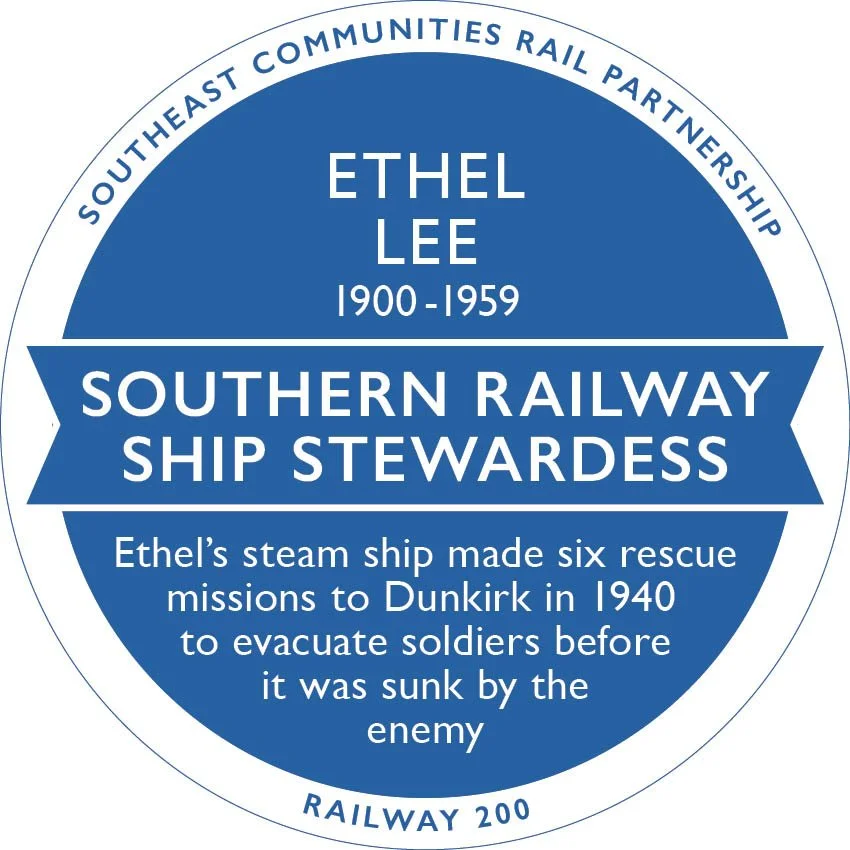

It’s the most personal stories that stick with you though: the death of a 7 year old on a railway crossing; a railway ship stewardess who spent 90 mins treading water in the Channel when her ship was bombed on the way to Dunkirk to help evacuate soldiers and a porter who played two rugby matches on his wedding day and lost a leg in WW2.

SCROLL ALL OR CLICK BELOW TO JUMP TO A SPECIFIC RAILWAY LINE

1066 LINE ↓

WINDSOR TO READING LINE ↓

UCKFIELD, EAST GRINSTEAD & OXTED LINE ↓

NORTH DOWNS LINE ↓

TONBRIDGE TO REIGATE LINE ↓

MARSHLINK ↓

HOUNSLOW TO RICHMOND LINE ↓

SUSSEX DOWNS LINE ↓

ARUN VALLEY LINE ↓

SUSSEX COAST LINE ↓

1-10

1066 LINE

Community Rail Line Officers - Andy Pope & Kanna Ingelson

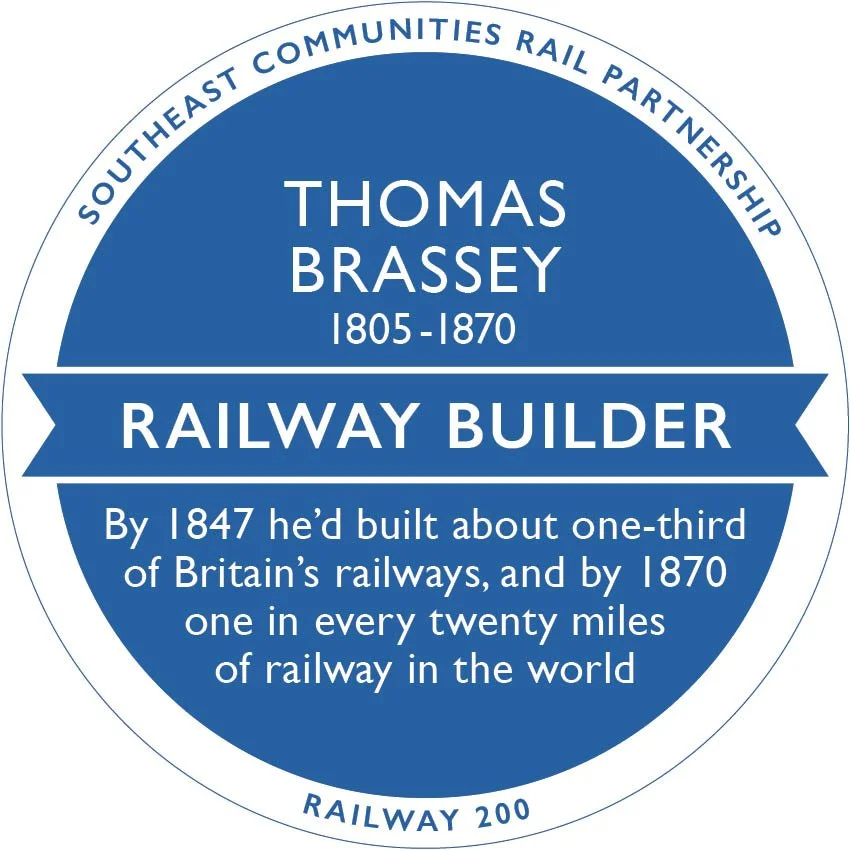

“At one point, Brassey had railway work progressing in Europe, India, Australia, and South America with a labour force estimated at 75,000”

-

b. Buerton, Chester 1805

d. St Leonards, East Sussex 1870“During a 40 railway building career he built one third of UK railways, three quarters of railways in France. 1 in 20 miles of the world’s railway network. Bridges, viaducts and stations” according to the Thomas Brassey Society.

In 1831 he married Maria Harrison, and they had three children: Thomas, Harry and Albert.

His career “began as an apprentice surveyor, then a partner and sole manager. In 1835 (aged 30) he built a section of Colorado railroad; assisted on the London to Southampton line; in 1841-43 he built the Paris-Rouen railway, and other lines in France, the Netherlands, Italy, Prussia and Spain; the Grand Trunk Railway in Canada (1,100 miles of track 1853-59) with Peto and Betts., as well as the Crimean Railway (1854).

At one point, Brassey had work progressing in Europe, India, Australia, and South America with a labour force estimated at 75,000. (Britannica)In the late summer of 1870 he took to his bed at his home in St Leonards-on-Sea. He was visited there by members of his work force, not only engineers and agents, but also navvies, many of whom had walked for days to come and pay their respects. (Tom Stacey biography)

On 8 December 1870 he died from a brain haemorrhage in the Victoria Hotel, St Leonards.

“Over and over again Florence replaced amputated limbs with an artificial one, and successfully induced the railway companies to receive these men again”

-

Florence Jessie Dolby was born in Kensington to retired army Capt. John and Jessie Dolby. She was a woman of independent means.

Around 1892 the necessary funds for a purpose-built railway Mission Hall and adjoining convalescent home for railway men on Portland Place, Hastings were raised from donations . Mission Halls were common nationwide for religious, social and Temperance classes but this was to be the very first convalescent home specifically for railwaymen.

In a promotional piece in a Mansfield newspaper of 1894 Florence, the Honorary Superintendent, described the Home hoping to encourage subscriptons and donations to help fund a much larger home.She wrote that 200 patients from 16 railway lines had already been treated in its first two years, though only 12 at a time. Some had suffered injuries or amputation following accidents, others were treated for “heart disease, influenza, rheumatism, and consumption being the most prevalent” though “no nurse was kept”, that task fell to Florence herself and two honorary doctors. The Home was supported by voluntary contributions. and “subscribers of one guinea are entitled to recommend one patient for three weeks at a charge of 5s. 6d. per week.”

An article in the London Echo in 1895 described how “the lady connected with it has over and over again first replaced the amputated by an artificial limb, and then successfully carried through the much harder task of inducing the railway companies to receive these men again, being quite as capable as before”.

The Home did move to much larger premises in 1897 where 40 beds could be accommodated. It was at 111 West Hill Road, St Leonards, close to Bo Peep junction, described in the Railway News as “one of the loveliest spots... standing on a cliff, overlooking the sea”. It was built on a site purchased by Miss. Dolby herself.

In 1901 Lancashire-born Jane Mercer was the nurse there with six other staff such as a cook and housemaids for its patients.

Florence retired from her work in her 50s through poor health. The following year she married the Home’s secretary the Rev. William Gray and they moved to Beckenham and later Rochester where she died in 1935, aged 85.

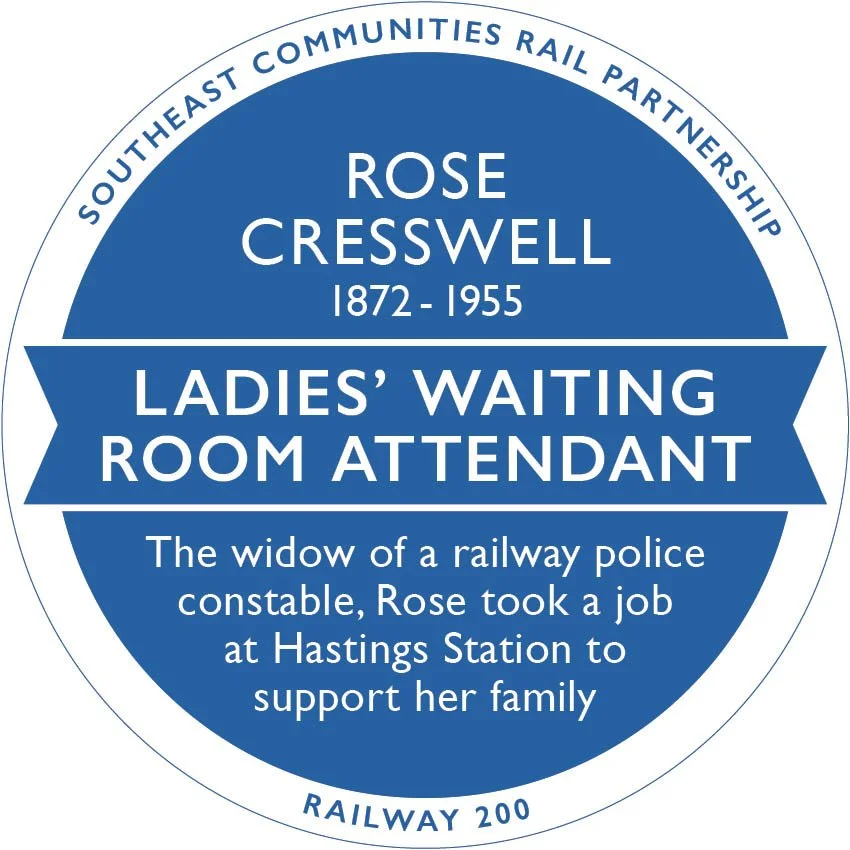

“Widowed at 46, Rose took work as a ladies’ waiting room attendant for at least 20 years”

-

Rose was born to Caroline and Henry Harris, a shepherd near Wanborough, Guildford in 1872, one of at least eight children.

She married Richard Cresswell, a railway porter, in 1901 and they were living in Dorking. They had a daughter Lilian and a son Richard Henry. By 1911 they’d moved to Mount Pleasant Road, Hastings and her husband was now a railway police constable. He died in 1918, aged 45, the cause is unknown.Now a widow Rose took a job as a ladies’ waiting room attendant at Hastings station. According to records, a job she still held in 1921 and 1939, and where she and now 28 year old son Richard (a wholesale grocer’s travelling salesman) had moved to Milward Road.

Rose died in Hastings in 1955 - some 37 years after her late husband. She was 82.

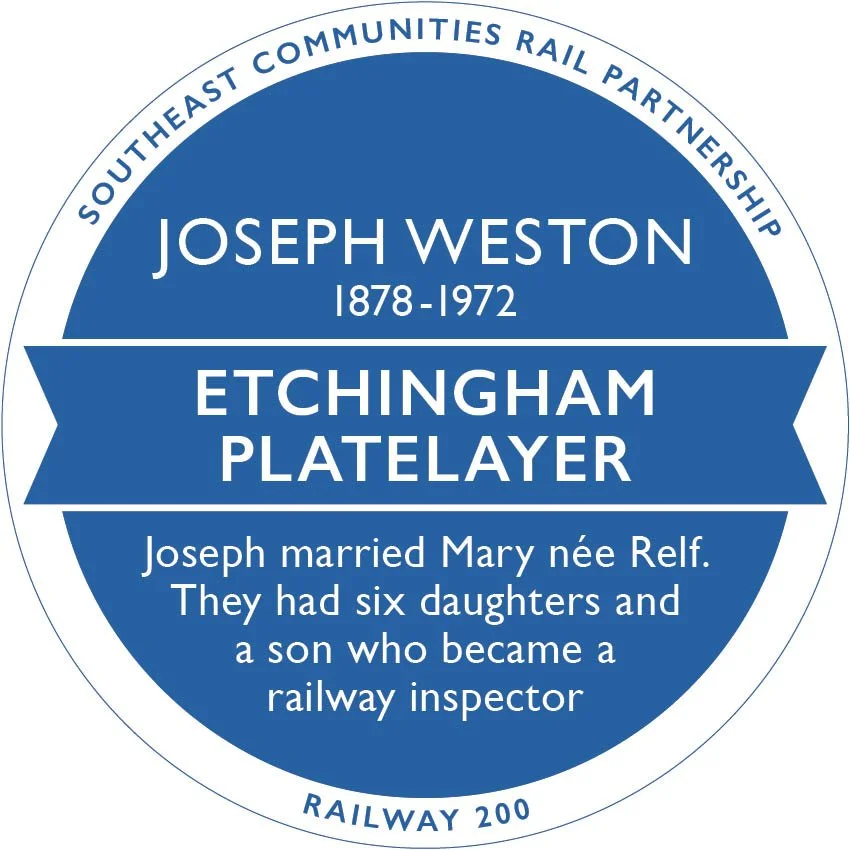

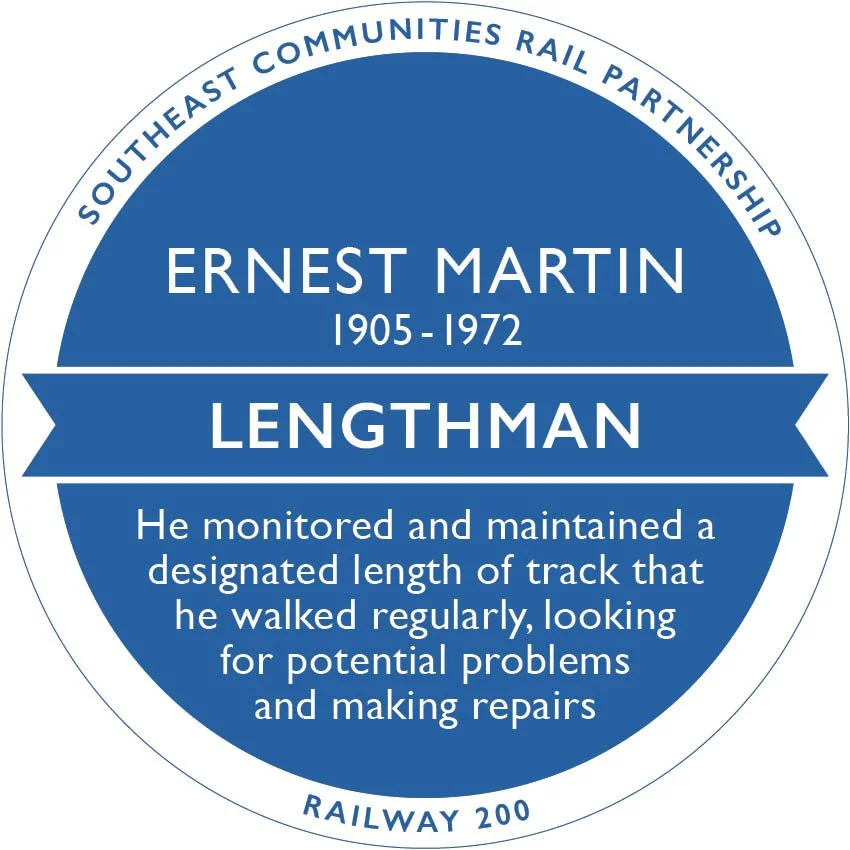

“In 1901 Joseph was living at Etchingham Station itself, where his father was a labourer at the creamery there”

-

Born in Ticehurst in 1878, Joseph was labouring on a farm by the age of 13, before becoming a railway labourer. In 1901, aged 22, he was still living at home - which at this point was Etchingham Station itself, where his father was a labourer at the creamery there.

Joseph married Mary Relf in 1904, and they had seven children - Irene, Olive, Albert, Evelyn, Marjorie and twins Bessie and Florence. From around 1921 to 1939 Joseph worked as a platelayer or lengthman for the railway around Etchingham, and living at 5 Rother View on Church Lane where it passes over the railway line.

Daughter Irene was living next door with her railway lengthman husband Ernest Wells at No 6! Son Albert was later living in St Leonards-on-Sea and was a railway engineer’s ganger for Southern Rail.

“Offering thrilling episodes, escapes, marksmanship and unique pastimes of wild west life the cast included 100 native American performers from the Sioux, Ogallallas, Brules, Uncapappas, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe tribes”

-

When Buffalo Bill’s touring Wild West extravaganza visited England in August 1903, its itinerary included Brighton, Guildford, Tunbridge Wells, Eastbourne, Hastings and on to Ashford and more of Kent.

For one day only, at each town stop, the hundreds of participants performed “twice daily, come rain or shine”, before dismantling and moving on by train to the next location.The local press advertisements declared Col. W. F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) would utilise four special trains to convey 500 horses and 800 people. Offering “thrilling episodes, struggles, escapes, adventures, marksmanship, and unique pastimes of Border life. 100 Redskin Braves, including the famous Warriors of the Sioux, Ogallallas, Brules, Uncapappas, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe tribes in Indian pastimes and Dances. Cowboys and Cowgirls in true pictures of the Western Plains... [a reenactment of] The Attack upon the Deadwood Stage Coach... and The Battle of San Juan Hill. All the exciting events of actual warfare and battle... Intense and vivid in its actuality. ... Buffalo Bill, the master exponent of horseback marksmanship, in his wonderful exhibition of shooting

while riding a galloping horse.” Sideshows included snake charming and the “human ostrich, who partook of repeated doses of indigestible articles”. When the Congress of Rough Riders of the World pitched their tents in Buckshole Field, Hastings on 20 Aug 1903, for example, “the weather in the evening was of the hurricane character but the performance was gone through all the same”.

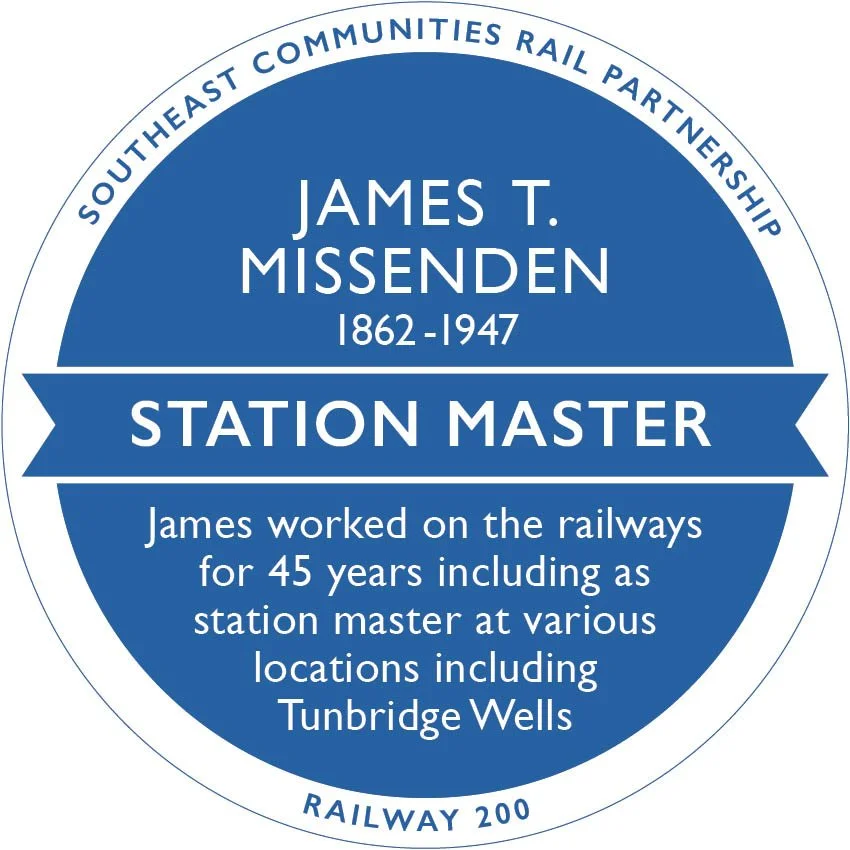

“James was President of the South East & Chatham Railwaymen’s ‘Undaunted’ Cricket Club. He and his wife Lucy celebrated their 60th or diamond wedding anniversary in 1943, and died just 10 weeks apart”

-

b. Bletchley 1862

d. Southborough 1947The son of a Bletchley labourer, James worked on the railways since he was about 18. Variously stationed at Westerham, London Bridge, Ashford, Folkestone Harbour and Bishopsbourne. Appointed station master at Bishopstone in 1901 followed by New Romney and Littlestone-on-Sea, Addiscombe Road Croydon and Blackheath. In 1917 became station master at Tunbridge Wells and Southborough in 1922, and after railway grouping he took over Tunbridge Wells West before retiring in 1927.

In the 1920s James was President of the South East & Chatham Railway men’s ‘Undaunted Cricket Club’In 1943 James and his wife Lucy née Alcock celebrated their diamond wedding anniversary (60 years). He died aged 85 at Carville Avenue, Southborough, Tunbridge Wells on 1 January 1947; his wife Lucy died just two months later on 12 March.

One of their children was Eustace Missenden.

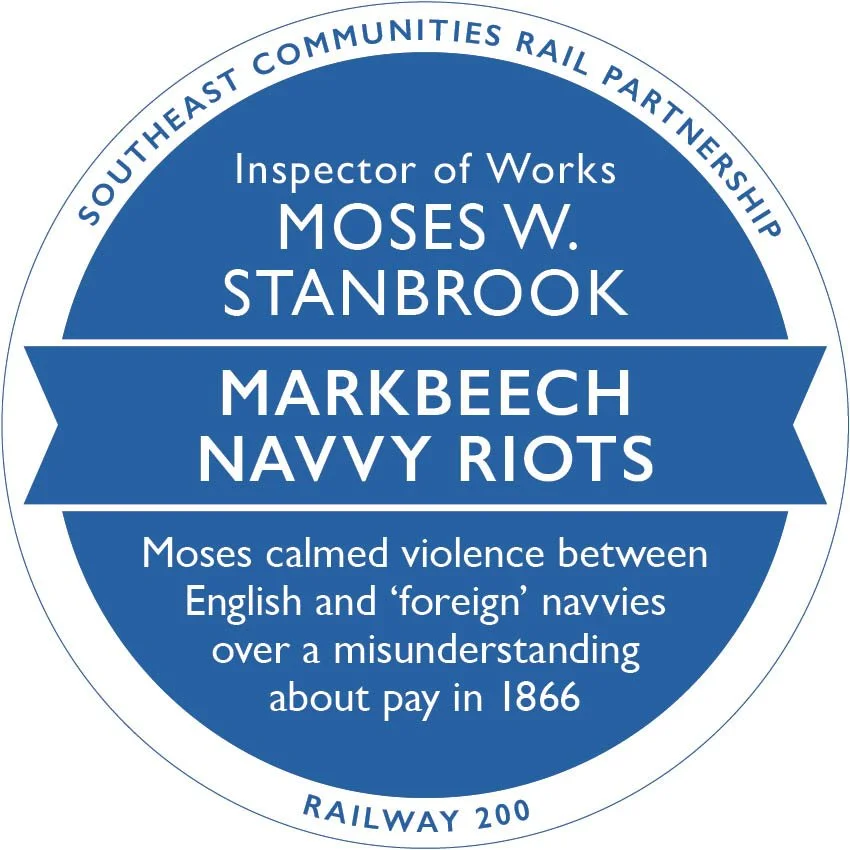

“At its height, around 250,000 navvies worked on the railways’ huge earthworks projects, and in the days before health and safety, thousands of accidents and many deaths occurred”

-

“Last Saturday [23 May, 1846] a lad, named Rock, met a dreadful accident on the railway works at Bopeep. One of the laden earth carts was being drawn over the bridge, and, as is usual, the horse unhooked a short distance from the ‘tip,’ when the lad fearing that the animal would run over him, jumped on the rails, and the cart came along and smashed his right leg in a shocking manner. He was taken as soon as possible to the Infirmary, where amputation of the injured limb was found necessary. At first slight hopes were entertained of the lad’s recovery, but we are happy to say that he is now going on well.”

Hastings & St. Leonards Observer, May 1846.Navvies were largely an itinerant workforce of manual labourers, originally excavating and building Britain’s network of ‘navigations’, the canals.These men were soon needed to build the railways, moving around the country wherever the work took them, where encampments were set up to house them. At its height, around 250,000 navvies worked on the railways’ huge earthworks projects, and in the days before health and safety, thousands of accidents and many deaths occurred. As early as 1839, Parliament wanted railway companies

to keep records of such injuries and fatalities on their construction sites. but not all did. And navvies weren’t necessarily considered railway employees and so could conveniently be excluded from the statistics.

Sadly we’ve been unable to identify Mr Rock or what happened to him.

“For Rye station building, William chose an Italianate style, and for Battle he gave a nod to the Abbey’s medieval architecture by facing the station in French stone from Caen”

-

b Faversham, Kent 1800

d Redhill 1859

Architect William already had experience of employing eclectic styles from a Gothic London church to a ‘plain’ London school. When the commission to design over a dozen railway stations in a short space of time for the South Eastern Railway’s new line from Tonbridge to Hastings he didn’t offer one template to be replicated. Some of the smaller stations were given a rather homely, brick building, while for others such as Rye (c.1850) he chose an Italianate style. In his design for Battle railway station, faced in Caen stone (1852) he gave a nod to Battle Abbey’s medieval architecture. He also created rural stations for Winchelsea, Appledore, Ham St, Wadhurst, Frant, Stonegate, Etchingham, Robertsbridge, Crowhurst and the original Hastings station which was replaced in 1931 (and again in 2004).

William had three daughters by his first wife Ann. After her death he had a son by his second wife Emma. William died in 1859 at his home Red Hill Lodge, in Redhill, Surrey.

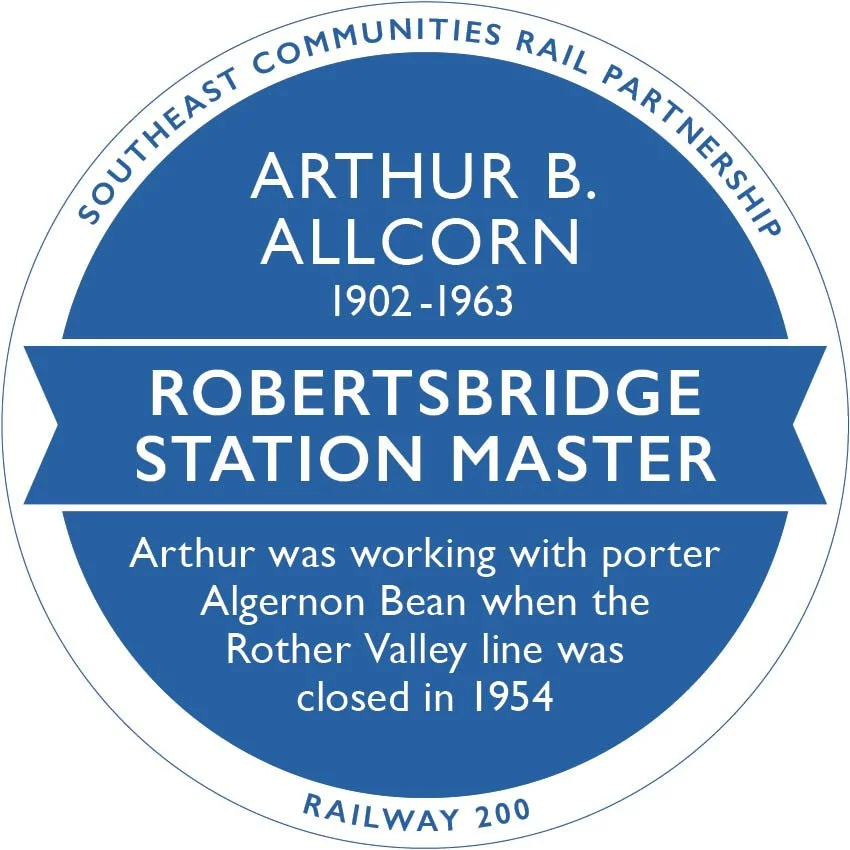

“One passenger recalled: one cold snowy day I travelled to the station in my high stiletto heels. Mr. Allcorn noticed and insisted I borrow his wife’s wellingtons”

-

Arthur Bertram Allcorn was born in Smarden in 1902, one of four children to Eliza and William, a domestic gardener. By the time Arthur was 19 he was a South Eastern & Chatham Railway booking clerk in Wye, Kent. He married Norah Ridley, and they had a daughter Rosemary. After a period in Tenterden Arthur was promoted

to station master at Robertsbridge.

One passenger recalls Arthur was “always very smart in his dark suit and peaked hat with gold braid trim. Mr. and Mrs. Alcorn lived in the house attached to the ticket office and had a large garden - where the extended car park is now. There were very few commuters in those days, but Mr. Alcorn was very protective of them. On the days my mother drove my father to the station Mr. Alcorn would ring up to let her know if the evening train was running late so that she was not kept waiting at the station. On one cold snowy day I travelled to the station in my high stiletto heels; Mr. Alcorn noticed and insisted that I borrowed Mrs. Alcorn’s wellingtons.”

On 2 January 1954 the single track Rother Valley Line between Headcorn and Robertsbridge closed after 50 years. On its final day over 1000 passengers rode the six-coach train with its two 1870s Stroudley Terrier engines, puffing along at 25 miles an hour. The driver was Fred Hazel, fireman Robert Blair and signalman-porter was Algernon Bean. Some passengers wore mourning dress, but the atmosphere was more of a picnic, a celebration with singing and numerous toasts, and at one station a shot gun salute rang out, at each level crossing there was a “cacophony of shouts and motor horns” and at another two bugle boys played the Last Post.

Arthur died in 1963.

“Working up the ranks from railway office boy to General Manager, Eustace was awarded an MBE, an OBE and a Knighthood, and a Southern Railway engine was named in his honour”

-

b. New Cross, London in 1886

d. Rudgwick, Horsham 1973Son of a station master, he began working life as a junior railway clerk. He married Lilian Gent in 1912. By the 1920s he was London District Traffic Superintendent for SE&CR. In 1935, he headed a contingent of railway officials on a trip to New York. He rose to become General Manager of Southern Railway, and later first Chairman of the Railways Executive.

He’d been awarded an MBE in 1925, an OBE in 1937’s Coronation Honours, and Knighted in 1944, having overseen the dispersal of over 180,000 troops by rail as they were rescued by small boats from Dunkirk.

Eustace even earned the honour of having a train named after him (featuring in a 1949 Pathe News segment). He died in 1973, aged 86.

11-20

WINDSOR TO READING LINE

Community Rail Line Officer - Sandy Mahon

“Lottie’s family had a bakery at 27 Denmark Street, Wokingham into the 1950s. After her death, a wooden footbridge was erected over Langborough crossing”

-

Seven year old Lottie Martin was out picking primroses with her sister Mary and their 19 year old nurse maid Ellen Bird on Wednesday 18 April 1883. At Langborough railway crossing Lottie sat on the stile as they waited for a luggage train to pass shortly before 6pm; she promptly jumped down to cross the tracks. But at the same time a London & South Western passenger train, running 3 minutes late and obscured by the first, was coming in the opposite direction. Totally unaware, Lottie was struck by it and killed immediately. The driver himself, Edmund Mann, didn’t realise what had happened until he received a telegram on his train’s arrival at Reading Station.

Lottie was born in Wokingham in 1876; the youngest of six children to Hannah Smith and local baker Henry Martin, whose bakery was at 27 Denmark Street, Wokingham for many years (where The Lazy Frog Massage shop is now). Her brother Weston, a fire brigade member and baker like his father, continued the family’s bakery business until his death in 1955.

A few months after Lottie’s death, a wooden footbridge was erected over Langborough crossing, and the Railway Co. decided to build a permanent bridge and a new station building at Wokingham.There’s a Wokingham Society blue plaque commemorating the unusual construction of the bridge in 1886 ‘from re-used rails’.

“Widowed Charles remarried and was actually living right beside Winnersh station. His son Ernest worked for John Warrick, the Cycle & Motor manufacturer making bodywork for three-wheeled delivery motor vehicles destined for Selfridges and the Post Office”

-

Charles was born in Slough in 1878, one of 9 children. He was employed as a cabinet maker, and married a lady called Elizabeth. By 1911 they were living at 70 Cromwell Road, Caversham with their two young children Ernest and Dorothy. Sadly Elizabeth died at 44. Charles remarried a couple of years later to Marian Parker and they had a daughter together, Marion Joyce.

By 1921, Charles and his family had moved to 19 Lorne Street in Reading. He was working as a carpenter and joiner for the Great Western Railway’s signal department on Caversham Road - possibly making the wooden semaphore signals, or even the woodwork of signal boxes themselves? Son Ernest, now 16, was a turner and fitter for John Warrick the Cycle & Motor manufacturer; who at the time was making bodywork for three-wheeled delivery motor vehicles destined for Selfridges and the Post Office.

Charles was still working as a railway carpenter during the Second World War, he was in his 60s, and was actually living right beside Winnersh station in 1939 (or Winnersh Halt as it was known then) at the house called Lockesley, at 19 Robin Hood Lane.

Daughter Marion’s husband Victor McLeonards was the son of an aeronautical engineer, and grandson of another railway carpenter at Caversham Road signal works - a colleague of his father-in-law Charles Sharpe!?

“Elsie’s piano making father was killed in action in 1916 when she was only 4. In the 1930s she worked for GWR, updating departure times and platform numbers”

-

Elsie’s mother Rosa Shuff was a housemaid until her marriage in 1911 to London piano maker Albert Lindsey. They were living in Finsbury Park when Elsie was born. Albert was called up for World War I in 1915 and was serving as a Private in the Royal Fusiliers when he was killed in action on 27 July 1916, aged 31. Elsie was only 4.

Rosa was from Caversham and she and Elsie moved back there during the war and by 1921 they were living with seven relatives at Rosa’s parents house Dean’s Farm Cottage, near the Thames. Elsie’s uncle Walter lived there too - he was an engineman for Great Western Railway. In 1939, aged 27, Elsie was working for GWR herself, as an indicator board operator - updating departure times and platform numbers. Elsie and her mother were living at 6 Erleigh Court Gardens in Earley by now.

Elsie married Norman Parlour in 1941 and appear to have had two children. Norman was a seedsman’s clerk - presumably at Sutton’s Seeds - a company who benefitted from the railway at Reading to handle large consignments of seeds and bulbs.

Elsie’s mother, who was widowed at 25, never remarried, and lived to the ripe old age of 100. Elsie herself lived to 2003, she was 91.

“In The ABC Murders each victim has a railway timetable left by the body; in 4.50 From Paddington a train passenger witnesses a murder in a slowly passing train; and in Murder on the Orient Express a murder occurs on a glamorous, snowbound train”

-

The best-selling novelist of all time - the writer of 66 detective novels - Agatha Christie loved train travel and was fond of using trains in her novels, as crime scenes for example. Sometimes they’re such a big character in the book they feature in the title. In The ABC Murders (1936) each victim has an ABC Railway Timetable left by the body; in 4.50 From Paddington (1957) a train passenger witnesses a murder in a slowly passing train; and in Murder on the Orient Express (1934) inspired by real events, a murder occurs on a glamorous, snowbound train.

Agatha and her first husband, businessman Archie Christie, moved to what had been described as an ‘unlucky house’ in Sunningdale in 1924. It was close to the railway station, so Archie could commute to his job in London. In 1926 Agatha’s mother died and a few months later Archie asked her for a divorce, having fallen in love with someone else.

In December Agatha’s car was found abandoned on the North Downs, close to where her husband was spending the weekend with his girlfriend. Agatha was feared missing, and a newspaper offered a reward for information.

In fact she’d had a nervous breakdown and used the train to ‘disappear,’ travelling as ‘Mrs. Neele’ - her husband’s lover’s name. She was discovered 11 days later in a Harrogate hotel having been recognised by staff.The following year Agatha began her next work - a Poirot novel called The Mystery of the Blue Train set on a luxurious train from London to the Riviera. She put her ‘unlucky’ Sunningdale home on the market and after her divorce was complete, she set of to see friends in Istanbul on the Orient Express...!

In 2023 as part of its ‘100 Great Westerners’ series GWR named the Intercity Express train 802110 ‘Agatha Christie’

“George had been serving in Palestine but his whereabouts were unknown and was presumed dead by his family. After his surprise return he retrained to work on the electrification of the railways”

-

George Edward William Gibbins was born in Oxfordshire in 1898 to Catherine and James Gibbins.

In his teens, George joined the Royal Army Medical Corp as a Private, marrying Elizabeth Gale on Christmas Day 1919. George returned to the army and served at their Headquarters in Lod hospital in Palestine in 1921.

Meanwhile back in England, his wife Elizabeth and their daughter were living with his parents in Kingston-upon-Thames. Elizabeth, now 24, was working as a pantry maid at a hotel, describing herself as a widow, suggesting George’s whereabouts were unknown and presumed dead. But happily George did survive his time in the army and the family were reunited.

By 1939 they were living at a house called Sonoma on Watmore Lane in Winnersh - with possibly four children. George, now 40, had retrained and was working for Southern Rail as an ‘electric track lineman’ as part of the railway’s electrification using the ‘third rail’ system as the region transitioned away from steam.

George lived until 1970, he was 71.

“Charles and Annie would have 8 children though only five survived. Their son Charles Jnr. became a gateman and porter, and grandson Cyril became an engine fireman and driver”

-

Charles was born in Dunsden in 1872, one of at least six children to parents Mary Ann Hamblin and husband Henry Willoughby, an agricultural labourer. After leaving school Charles worked on a farm, marrying Annie Purton in 1896.

By the time of the 1911 census, now aged 39, Charles described himself as a railway labourer and platelayer (laying and maintaining the tracks) and living with his family at Matthews Green, Wokingham. Charles and Annie would have 8 children in all, though only five survived: Sons Edmund and Charles and daughters Elsie, Gertrude and Lilian. Lilian went on to marry Reginald Brown, a former railway navvy - a tough, often dangerous, job of heavy, manual labour, building railway bridges, cuttings and tunnels, with little more than picks, shovels and gunpowder.

A decade later Charles is still platelaying, with the family now living at 144 London Road, Wokingham (opposite Froghall Green, where St Crispin’s School is now). He died in 1932, aged 59.

His son Charles was a railway gateman - manning level crossing gates - for South Eastern, though by 1939 he’d become a railway porter with office duties, and particularly at Winnersh Station after WWII. He was living at 9 Barkham Road, just yards from Wokingham Station (and Lottie Martin’s railway bridge!) with his wife Edna May and their seven children including Gladys, Leonard and Cyril.

Cyril Willoughby (Charles’ grandson) started working on the railways himself when he was 15 years old, becoming a ‘fireman’ on the steam trains when he turned 16. He went on to drive trains from the age of 23 - steam trains initially and later diesels and electric - working the Reading-Waterloo line through Winnersh much of the time - until his retirement.

“Two race day trains collided, crushing the guard’s van at the rear to ‘splinters’. Victims’ injuries were often described in the newspapers in all-too-vivid detail. Five men died at the scene, the sixth died a few days later”

-

A racecourse, a ‘Royal Racecourse’ at Ascot was first established in 1711 by Queen Anne. With the coming of the railways Ascot station opened in 1856, welcoming its first race-goers by railway in 1857.

Ascot’s first day of racing in 1864 was Tuesday 7 June. The Prince and Princess of Wales (the future King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra) were in attendance. Racing had been running late and railway officials were concerned about the sudden rush of passengers. Trains were run rapidly one after another. There was an on-board altercation at Egham about card sharpers on one train which lead to a short delay, but it was enough for another crowded train behind to catch up, despite it not travelling at a great speed. At about 7.45pm these ‘special’ race day trains collided, crushing the guard’s van at the rear to “splinters” but luckily the guard had jumped clear. Described in the Buckingham Advertiser as “those long, unmanageable trains, heavily laden with holyday makers”.

Five men died at the scene, a sixth dying from his injuries a few days later. Injuries were often described in the newspapers in all-too-vivid detail that we shan’t repeat here.Those who died were: William Winfield, gardener to Mr Bracebridge, Sherbourne; Edwin Hall, corn chandler, 6 Duke St, Manchester Sq, London; John Cobbett agent to racing celebrity Mr Padwick, Hill St, Berkeley Square, London; Robert Wilkie, publican Glove Inn Kings Road, London; Joseph Clegg, publican Harp Inn, Jermyn St, London; Esau Trigg, Brighton publican (Hero of Waterloo Inn) 34 Lower Market Street, Hove - died a few days later at Charing Cross hospital

“At first treated with suspicion and hostility, eventually she was just one-of-the-boys and welcomed into the card games in the smokey mess room.

‘What can compare to the view from the front cab of a train rushing through a snowstorm at 90 mph’”

-

Born in Sussex, Helena trained as a GPO switchboard operator, which led to a job as a telephonist in British Rail’s Southern Region at Waterloo in 1977. She realised very quickly that the job didn’t suit her. She disliked being on the periphery of the railway industry not in the thick of it.

Stories of a colleague’s husband’s new career as a guard piqued her enthusiasm. The Sex Discrimination act had come into force a couple of years before - promoting equal opportunities regardless of gender - so encouraged by her female colleagues to become the ‘first lady guard’ Helena filled in the application form.

Needless to say her application progressed grudgingly; they hoped a medical exam and tough training courses would weed her out as an inadequate candidate but she passed them all. She was in! On her week’s induction, obviously the only woman, she learnt first aid, and about railway rules and laws.Between courses she did a stint at Wimbledon Station. Her first uniform was a male guard’s jacket with jeans and Doc Marten boots. She was treated as a celebrity, the first woman ‘learner-guard’ and treated as one-of-the-boys. On the a shunter’s course she met some hostility. Accused of taking work away from a man. On this course Helena recalls she “had to lift a notoriously heavy ‘buckeye’ coupling’ ... too heavy for any woman to lift. A semicircle of tormentors gathered around sniggering when my turn came. I knew this was the end of my brief sojourn on the ‘real’ railway: not only would I never be a guard, I would exit utterly humiliated and to a chorus of jeers and ‘told-you-so’s’ from my harassers.The thought of this, and the feeling that all women would be judged on my success or failure, gave me the strength to lift it. But there was no applause and no apology.”

The guard’s course followed. Learning how “all the various signalling systems worked, and procedures for dealing with every emergency that could possibly arise: collision, fires, signal problems, derailments, drunks, drug-takers, objects on the track”. She passed with 80% and moved to her depot,Wimbledon Park, where she met a little animosity, “especially from those who had failed the guards’ course”. She was even accused of getting the job through favouritism. Six weeks ‘on the road learning’ involved accompanying senior guards on their shifts, day and night. She was welcomed into the card games in the smokey mess room.

“Seeing the sun rise over a Berkshire field covered with rabbits and set over the Solent were magical experiences.And what can compare to the view from the front cab of a train rushing through a snowstorm at 90 mph” she says.

Sixteen weeks since her application, on 23rd March 1978, she worked her first train alone.The 12:46 return Waterloo to Windsor. She was still only 19.

In her spare time Helena had studied for a degree in Sociology and Social History and she became a full-time historian following a railway career-ending accident in 1999. Her particular focus has been on Victorian women, publishing several books on the subject, including her well-regarded book ‘Railwaywomen’ which took 10 years of research into their hidden histories.

Read Helena’s full reminiscences on the beginnings of her railway career at hastingspress.co.uk/railwaywomen

“Brunel’s French father fled France for the USA during the Revolution and was appointed Chief Engineer of New York City. Back in London he worked on the first tunnel under the Thames with his son Isambard, who at one point was severely injured. During a six month recuperation he worked on designs for a competition to create a bridge across the river Avon in Bristol”

-

Brunel’s French father Marc fled France for the USA during the Revolution and was appointed Chief Engineer of New York City. He moved to London in 1799, married Sophia Kingdom, and was Knighted for the difficult and dangerous building of the Thames Tunnel (now connects Rotherhithe and Wapping Overground stations).

His son Isambard was born in 1806 and picked up his father’s aptitude for mechanics. His education included a boarding school in Hove and the University of Caen, France and later in Paris. He assisted his father on the Thames Tunnel and was severely injured as a consequence. During a six month recuperation he worked on four designs for a competition to create a bridge across the river Avon in Bristol. His winning design would become the Clifton Suspension Bridge - though its construction wasn’t completed in his lifetime, and the designs had been somewhat altered by other engineers.

Other projects of his include the first transatlantic steamship ‘The Great Western’ as well as tunnels, viaducts and bridges most notably for the Great Western Railway such as the brick arched Maidenhead Railway Bridge (1839) and the wrought iron Windsor Railway Bridge.This was opened in 1849, the branch line having been delayed following objections by the Provost of Eton. He demanded no station be built within 3 miles of the college, fearing the College would be ruined because “London would pour forth the most abandoned of its inhabitants to come down by the railway and pollute the minds of the scholars, whilst the boys themselves would take advantage of the short interval of their play hours to run up to town, mix in all the dissipation of London life, and return before their absence could be discovered.”Brunel’s iron bridge is a bowstring-arch-truss construction, 61m in length, in the middle of a brick-built 1500m long viaduct, described in the press at the time as “of novel design”.

It’s the world’s oldest surviving wrought iron bridge (incidentally, the oldest cast iron bridge is Abraham Darby’sacross the Severn gorge dating from 1781 at what is now the village of Ironbridge)

“It is worth being shot at, to see how much one is loved”

-

Queen Victoria had returned from London on the train to Windsor station where she transferred to a carriage to continue on to the Castle. A large cheering crowd of on-lookers had gathered including a group of boys from Eton school. “There was a sound of what I thought was an explosion from the engine, but in another moment, I saw people rushing about and a man being violently hustled, rushing down the street” the Queen later wrote.

It was the sound of a gunshot from a pistol she’d heard, triggered by a culprit “who was very miserably clad”. Two of the Eton scholars Gordon Wilson and Leslie Murray Robertson/Robinson, ‘brave, stalwart boys’ had tackled the would-be assassin Roderick Maclean. Wilson struck Maclean’s weapon with his umbrella while Murray Robertson wrestled him, undoubtedly preventing a second shot, and saving the Queen’s life. According to one press account the pistol was not “heavily loaded, and did not take effect.” Maclean was apprehended by Slough’s loco department foreman John Frost who had accompanied the Royal train.

30 year old Maclean was the last of seven men who’d made attempts on the Queen’s life. He’d left a written statement that morning to say he had no intention of causing Her Majesty any injury, just to cause alarm and draw attention to his ‘pecuniary straits’. Witness statements proved the revolver was bought from a pawnbroker for 5s. 9d. in Portsmouth. His father had had him examined some years before to ascertain if he was of sound mind and had been confined in a Weston-super-Mare asylum for 12 months suffering from insane delusions, with homicidal mania. He was found not guilty of High Treason on grounds of insanity, and spent the rest of his life in asylums.

The public outpouring of support lead to Queen Victoria writing to her daughter Vicky saying:‘It is worth being shot at, to see how much one is loved.’

BACK TO TOP

21-30

UCKFIELD, EAST GRINSTEAD & OXTED LINE

Community Rail Line Officer - Sharon Gray

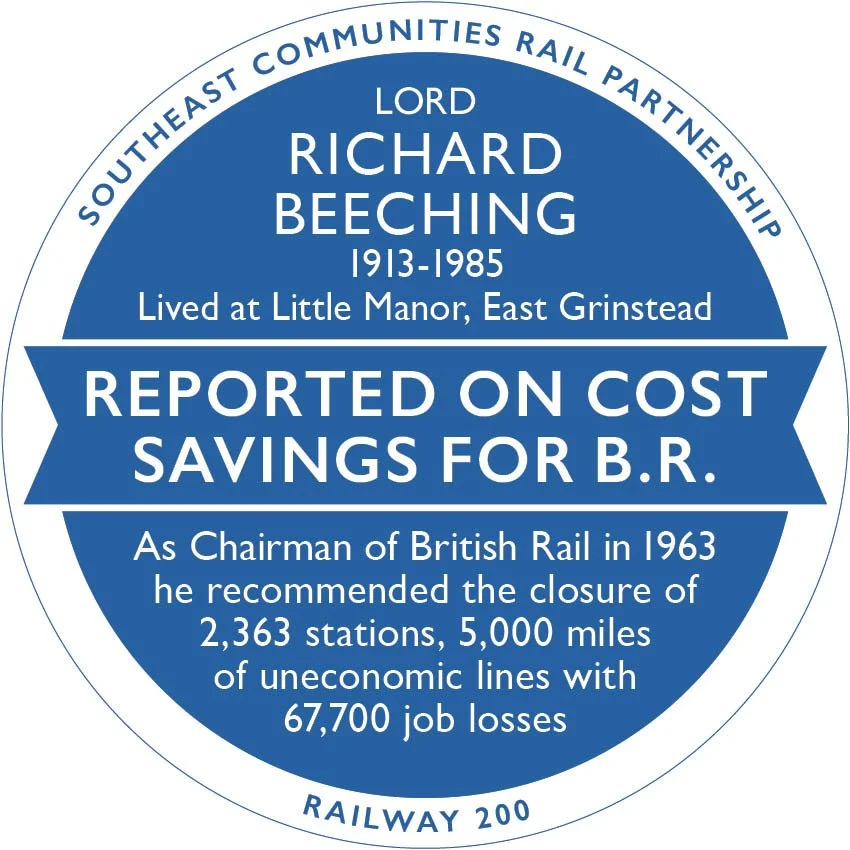

“Beeching’s report was sponsored by the Transport Minister who introduced yellow lines and traffic wardens, a Minister with financial interests in tarmac and road building”

-

One of four sons born to Annie Twigg and Hubert Beeching, a newspaper sub-editor.

Richard was born in Sheerness but his family moved to Maidstone during the war. He was a prefect

at grammar school, studied physics at Imperial College, London and then a PhD. He was senior researcher for nickel extractors Mond Nickel Co. in Birmingham where he lived with his wife Ella.

During WWII he worked on armament design which lead to senior jobs at ICI. In the 1950s freight transport by road was increasing, rail freight revenue was decreasing, causing unsustainable financial losses. By 1960 Richard joined the British Transport Commission’s advisory group on the running of railways, sponsored by the Conservative government Transport Minister Ernest Marples (who introduced the MOT test, yellow lines and traffic wardens for example). Controversially Marples had financial interests in tarmac and road building - a potential conflict of interest?

In 1963 the Commission, reframed as the British Railways Board, concluded that more station and line closures (that had already begun in the 1950s) could save the loss-making network a great deal of money. Their clinical calculations were doubted and challenged, in one example by a 12 year old boy, and their solutions were opposed by the public by 5 to 1. Alternative suggestions to large-scale closures were proposed such as using much shorter trains off-peak to greatly reduce wear and tear costs. But the ‘Beeching Axe’ was largely enacted over the coming years. In 1965 Beeching unveiled the newly branded British Rail, and was made a life peer ‘Baron Beeching’.

He was living at Little Manor, Lewes Road, East Grinstead when he died at Queen Victoria hospital in 1985.

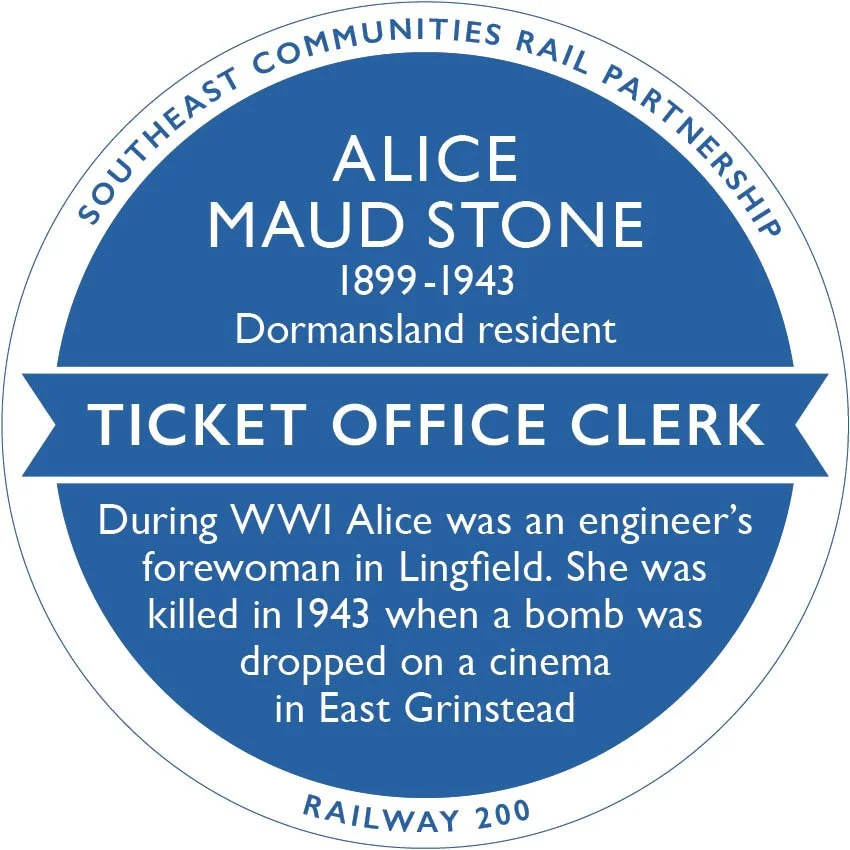

“At 5.10pm on Friday 9 July 1943, as an audience of mostly children were enjoying Hop-Along-Cassidy, a bomb was dropped on Whitehall cinema, killing four women- Alice Stone, Florence Firmin and Erica and Mary Fothergill”

-

Alice was the youngest of five children to house decorator Pharoah Stone and his wife Emily. They were living on Dormans High Street in 1901. Around 1916 Alice worked as a railway ticket office clerk at Dormans station. By 1921 she was the last child still at home, aged 21. She had been working and forewoman for Mr Hales’ engineering company in Lingfield.

She married gas meter inspector Joseph Meadmore in 1931. They had three children Patricia, Joe and Bobbie by 1939 and were living on Sackville Gardens, East Grinstead.During WWII on Friday 9 July 1943 the German enemy approached the town for a daylight bombing raid on East Grinstead. Air raid sirens sounded and the corresponding announcement flashed up on the screen of the Whitehall Cinema. At 5.10pm bombs were dropped on the High Street, destroying shops and the cinema where an audience of 184, many of them children were watching ‘Hop-Along-Cassidy.’

Alice was inside, one of the four adults killed. By chance many of the children owe their lives to being seated at the front of the cinema. Overall 108 people died in that raid, 235 seriously injured. Twenty two of those killed are buried in a communal grave in Mount Noddy Cemetery.There’s an inscription in Dormansland Parish Church to the four women who lost their lives that day: Alice, Florence Firmin and Erica and Mary Fothergill and those civilians of Dormans Land who died in the service of Civil Defence units 1939-45.

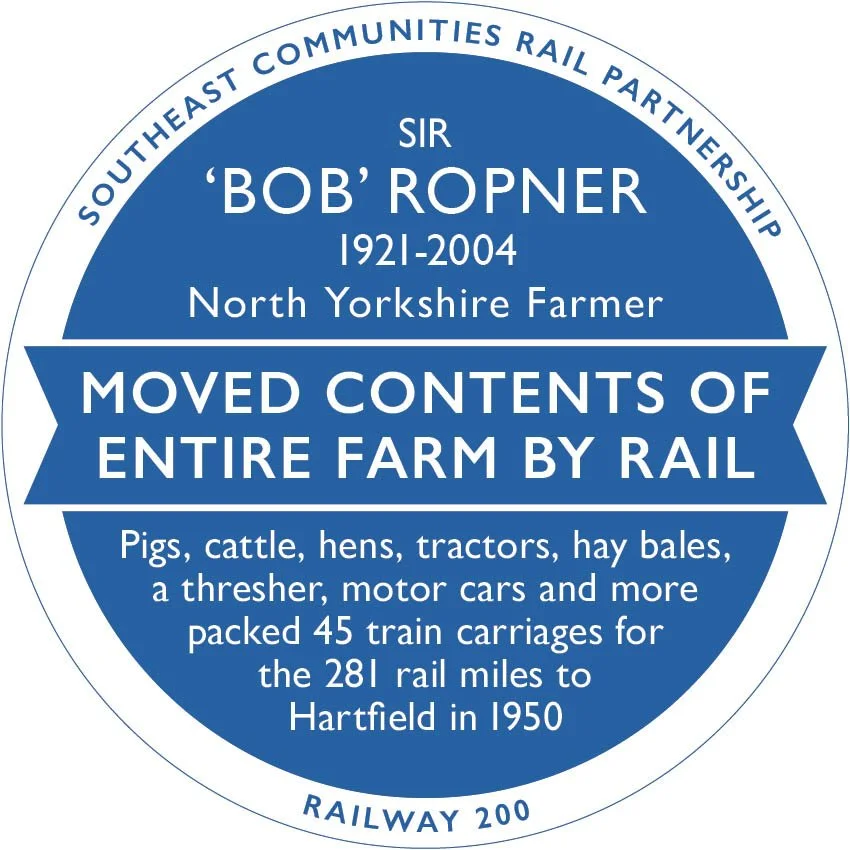

“The move took place overnight in December 1950, there was snow throughout the journey, it took 18hrs 30 mins. A British Transport film crew beautifully recorded the logistical feat of relocating a whole farm across the country by rail”

-

A short British Transport film from 1952 beautifully records the logistical feat of relocating a whole farm, belonging to Robert Douglas Ropner, from one end of the country to the other.

Ian Pearce of the Kirby, Great Broughton and Ingleby Greenhow Local History Group writes that

it “showed the owner of White House Farm, Skutterskelfe, moving all the machinery and all the livestock of his farm as well as household goods and furniture by train from Stokesley Station to Hartfield Station in Sussex and then taking over Perryhill Farm, Sussex... The move took place in 1950 in December and there was snow throughout the journey, which was overnight and took 18hrs 30 mins. 50 wagons were needed and the train was divided into 2 at some point on the journey, the second half following later. The film was narrated by A. G. Street and released in 1952.”The farm was part of the Skutterskelfe estate owned by the Ropner family of shipbuilders and shipowners, and the farmer was no ordinary North Yorkshire farmer but Bob Ropner, a member

of the family. The farm bailiff... Henry Hill... was the only employee from North Yorkshire to move permanently south with the farm. He and his family settled in the south and stayed there even after Bob Ropner gave up farming himself in 1954.

Ropner then started a catering business, but it had little success and he re-located with his family to Switzerland. Inspector Barr, who was the British Rail manager of the journey, returned to Middlesbrough after completing the transfer and the farm workers - looking after the cattle, bull, pigs, ducks, chickens and cat - all returned home to North Yorkshire.”The farmer Robert Douglas Ropner married to Patricia K. Schofield in 1943, they had a son called Robert C. in 1949 who appeared in the film as a baby.

Robert’s grandfather, the original Sir Robert Ropner (1838-1924) was born in Magdeburg, lost his parents to cholera, went to sea but suffered from seasickness and so abandoned his sailing career when he arrived at Hartlepool. There he settled, marrying a local baker’s daughter and gradually building up his business interests to become a shipping magnate.”

Watch the film at the BFI website for FREE here (17 mins): https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-farmer-moving-south-1952-online

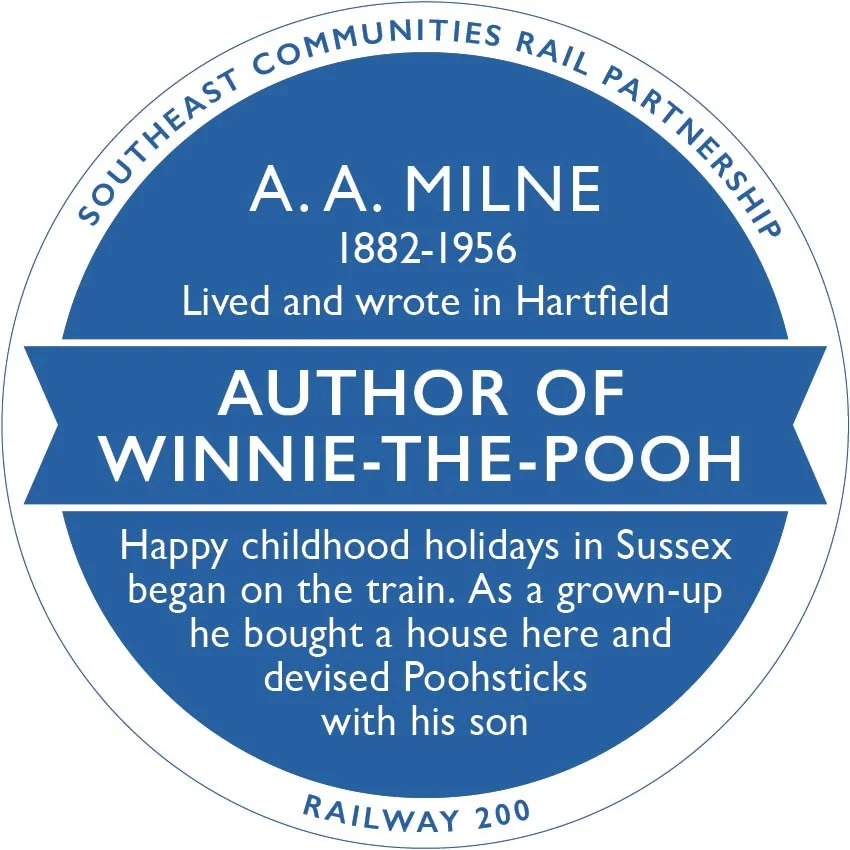

“‘I stand at the door of my carriage feeling very happy. It is good to get out of London. I have nothing to read, but then I want to think. It is the ideal place in which to think, a railway carriage; the ideal place in which to be happy’”

-

“I stand at the door of my carriage feeling very happy. It is good to get out of London. I have nothing to read, but then I want to think. It is the ideal place in which to think, a railway carriage; the ideal place in which to be happy.”

A.A.MilneAs a child, living in Kilburn in London, young Alan Alexander Milne and his brother were often brought out by train from Victoria station into the woods, valleys and fields of Sussex by their father for countryside walks and adventures. Alan recalled that as an 8 year old they once walked 19 miles in a day - fuelled by nuts, ginger beer and ham and eggs - they took in Edenbridge, Hever, Chiddingstone and Cowden station where they took a train to Tunbridge Wells. And before going away to Cambridge University around 1901 he spent time in Hastings where his uncle Alexander was teaching.

By now Alan was writing humorous verse for Punch magazine, and went on to write plays and novels. He married Daphne in 1913, joining the British Army for World War I - as a signals officer at the Somme - but was invalided out. Eventually he was recruited into intelligence to write propaganda.

He and Daphne had a son Christopher Robin in 1920. They left the bustle of the metropolis for the serenity of Cotchford Farm in Hartfield in Alan’s beloved Sussex. It was here that a five acre wood in Ashdown Forest became the fictional Hundred Acre Wood where he would set the stories about a young boy who befriends a bear and other characters. Inspired by a real life bear - the tamest army mascot named Winnie, who had been deposited at London zoo by an army officer from Winnipeg. Christopher Robin was able to befriend Winnie at the zoo, and this inspired his father’s famous Winnie-the-Pooh books.

On National Poetry Day 2017 Tony Knight, a South West train announcer in Wokingham, read AA Milne poems to waiting commuters.

Although he didn’t put Winnie-the-Pooh on a train Milne was clearly a fan. Writing “Nowhere can I think so happily as in a train” he wrote “I am not inspired; nothing so uncomfortable as that. I am never seized with a sudden idea for a masterpiece, nor form a sudden plan for some new enterprise. My thoughts are just pleasantly reflective. I think of all the good deeds I have done, and (when these give out) of all the good deeds I am going to do. I look out of the window and say lazily to myself, “How jolly to live there”; and a little farther on, “How jolly not to live there.” I see a cow, and I wonder what it is like to be a cow, and I wonder whether the cow wonders what it is to be like me; and perhaps, by this time, we have passed on to a sheep, and I wonder if it is more fun being a sheep. My mind wanders on in a way which would annoy Pelman a good deal, but it wanders on quite happily, and the “clankety-clank” of the train adds a very soothing accompaniment. So soothing, indeed, that at any moment I can close my eyes and pass into a pleasant state of sleep.”

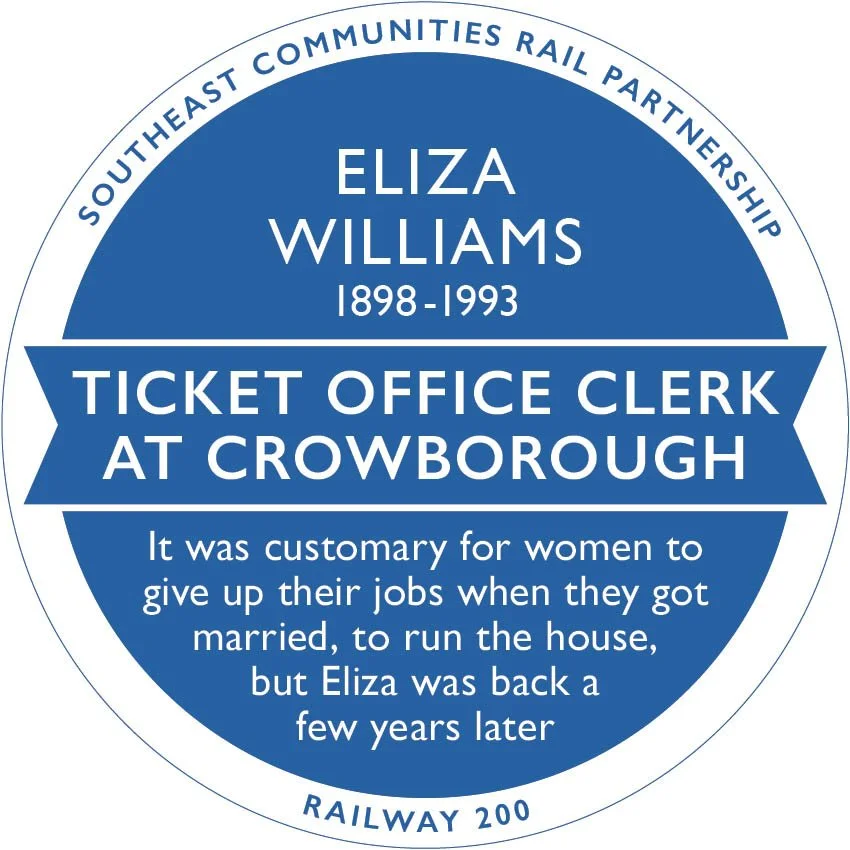

“From 1916 Eliza was a ticket office clerk at Crowborough and then at Rotherfield for the London, Brighton & South Coast railway. She gave up her job when she married in 1926, returning four years later”

-

Eliza Louisa Williams was born on New Road, Rotherfield around 1898, the only child to Ellen Izzard and Arthur Williams, a railway platelayer and underman.

From 1916 she was a ticket office clerk at Crowborough, and continued in that role at Rotherfield for the London, Brighton & South Coast railway according to the 1921 census. Around this time the family, still on New Road, had a lodger, one of Eliza’s fellow railway clerks called Gladys Carpenter.In 1926, ten years into her job, Eliza married a nursery gardener and fruit grower called Harold Hammond. He appears to be the youngest of nine children, and had been working as a gardener since he was at least 14. He was wounded while serving in the First World War.

In those days it was expected of a newly married woman to give up her job to have a family and run the marital household. Eliza was no different. However it seems they had no children and this may have contributed to Eliza returning to work four years later. By 1939 they were living near Harold’s plant nursery in the village of Town Row close to Rotherfield station, just a few doors from the Railway Inn. She lived to 95.

“So respected was William that in the church a brass inscription dedicates a small memorial window of stained glass to him of the Prophet Daniel with the words “Was weary’ now at rest” - both paid for by friends and admirers”

-

Born in Hertfordshire in 1826, William married Lydia Brace in Ware in 1843. They don’t appear

to have had any children, none that survived at any rate. By 1851 William was a railway porter at Edenbridge and had progressed to station master there a decade later. In fact he was still station master there over 25 years later upon his death on 29 September 1884, aged 58. Tragically followed just a few weeks later by Lydia on 7 December.Friends erected a simple Latin cross, recumbant, on his grave as a mark of respect. And in the church a brass inscription dedicates a small, “chaste” memorial window of stained glass (by Ward & Hughes) of the Prophet Daniel with the words “Was weary’ now at rest”. The window and plaque were paid for by friends and admirers.

“Established by philanthropists around 1899 as a training school for poorer epileptic children - during the first war adult men needing the Colony’s specialist care services were admitted too. By 1939 it was home to almost 500 patients, Samuel being one of them, until his death in 1940, aged 61”

-

Samuel Archibald Collins was born in the St Pancras area of London in 1879. He worked as a labourer and carman on the railways there. He married Sarah Arnold in 1901 and they had two children Alfred and Florence. He enlisted in July 1916, as a Private, assigned to the Labour Corps of the 520th Home Service Employment Co. providing essential war work on home soil. It’s not known what happened to him but two years later aged 41 he was declared physically unfit to continue. Curiously he hadn’t returned to his wife and family by 1921. In fact he was an ‘inmate’ as they called it, at the Epileptic Colony in Lingfield.

Established by philanthropists around 1899 as a training school for poorer epileptic children - with a capacity for learning - who might otherwise find themselves in senile wards of a workhouse.

According to an article in the British Medical Journal, in its 300 acre site, the colony provided teachers and medical staff, a schoolhouse, and training in laundry, carpentry and gardening.

Treatments included medicines such as bromide, as appropriate of course, as well as regular employment; as much fresh air as possible; organised games and amusements such as concerts; the interest and discipline of school; a largely vegetarian diet and an ‘abundance of sleep’.

Usually home to hundreds of children and youngsters, led by the matron Nora Henson and school teachers Katherine and Annie Caston; suddenly in wartime dozens of men, presumably with brain injuries and symptoms akin to epilepsy, needed the specialist care services on offer too.

Of the 400 inhabitants in 1921, there were other railway workers such as platelayer Harold Trivett, railway fireman Wilfred Stevens and shunter Frederick Sandles, but also the likes of Walter Lucas the footman to Baroness Wedel Jarlsberg and a grocer’s assistant from Selfridges. By 1939 the colony was housing almost 500 patients, Samuel being one of them until his death in 1940, aged 61.

“The bomb comprised of a two-gallon can of fuel inside a travelling basket, attached to an alarm clock set to trigger a fuse at 3am. Crucially an address label on some brown wrapping paper at the scene would lead to a key suspect”

-

Born in Godstone in 1884 to a cattle dealer, Edwin worked initially as a milkman in Horley. By 1911 he was a railway porter living on 2 Marsland Cottages, Station Road, New Oxted with his wife and a daughter, both called Maggie, and a lodger.

Emmeline Pankhurst, the political activist and chief campaigner for British women’s suffrage (the right to vote in public elections), was found guilty on 3rd April 1913 of inciting arson and using bomb tactics, and sentenced to 3 years ‘penal servitude’.

The following morning, Friday 4th April 1913 Edwin Mighell went in to work at 6.30am. He found the gentleman’s lavatory badly damaged, walls bulged out and the roof blown off. It was discovered that an improvised explosive device had gone off during the night, but luckily had failed to work as intended and no-one was hurt.

Comprising a two-gallon can of fuel inside a travelling basket, attached to an alarm clock set to trigger a fuse at 3am. Additionally there was a flask of cycle lamp oil, a slough hat, a firelighter and some saturated cottonwool. Outside a nickel-plated pistol was found that accidentally went off in the postman’s hand, fortunately doing ‘no mischief’. The lavatory adjoined the station’s oil store, so had a fire broken out that would’ve been quite an inferno.

No Suffragist pamphlets were left at the scene, as was often the case, but some brown wrapping paper that would’ve been destroyed was found intact with a department store label and the name Mrs Watkins. Through store records the police tracked down Mrs Watkins’ delivery address, it appeared that her jeweller husband had reused the paper to send a mended item to a Miss Frida Kerry. Frida and her parents were suffrage sympathisers but confessed nothing. Only much later in 1950, after the death of her husband Harold Laski (a professor at the LSE and Labour Party Chairman 1945-46), did Frida finally admit that it was Harold that had planted the bomb.

In July 1932, Edwin’s wife Maggie, the mother of his five children, died of heart failure while hanging out the washing. Edwin married again in 1934, to Martha Riddle, but he died in 1937, aged 53, having been stationed at Oxted for 32 years.

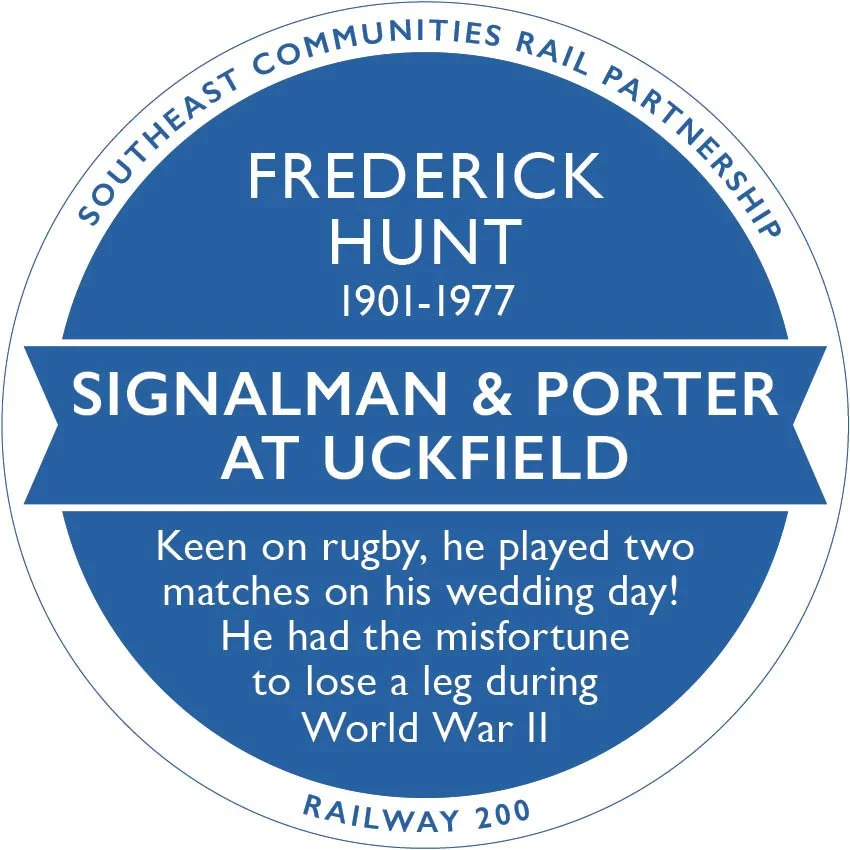

“At Uckfield railway crossing in 1934 an impatient motorcyclist died colliding with crossing gates as they were closed in anticipation of an oncoming train. Porter Frederick dragged the deceased and his motor cycle clear of the line ensuring the safety of the imminent train and its passengers”

-

The son of an Eastbourne dustman born in 1901, Frederick was working as a barman at the King’s Arms Hotel on Seaside, Eastbourne in 1921 before getting a job at Uckfield railway station.

He married Dorothy Gladys Ashman in 1926 but being a very keen rugby right half for Uckfield, he played two matches on his wedding day, one in the morning and another after the Register Office ceremony! The Club gave the happy couple a biscuit barrel as a wedding present, and colleagues at the railway station gave a tea service. They had two children and lived their married life on Vernon Road, Uckfield.

An incident occurred at Uckfield railway crossing in 1934, where an impatient motorcyclist died colliding with crossing gates as they were closed in anticipation of an oncoming train. Porter Frederick, hearing the screeching and crash “dashed down and dragged the deceased and his motor cycle clear of the line” ensuring the safety of the imminent train and its passengers.

Joining the Royal Engineers to participate in World War II, he served in France, where he was involved in ‘Little Dunkirk,’ the evacuation of over 21,000 troops from the fortified town of St Malo in 1944. Afterwards he was sent to North Africa where he had the misfortune to lose a leg, but returned to Uckfield where, with the assitance of an artificial leg, he was able to resume work, now as a signalman.

He retired in 1967 and died aged 76.

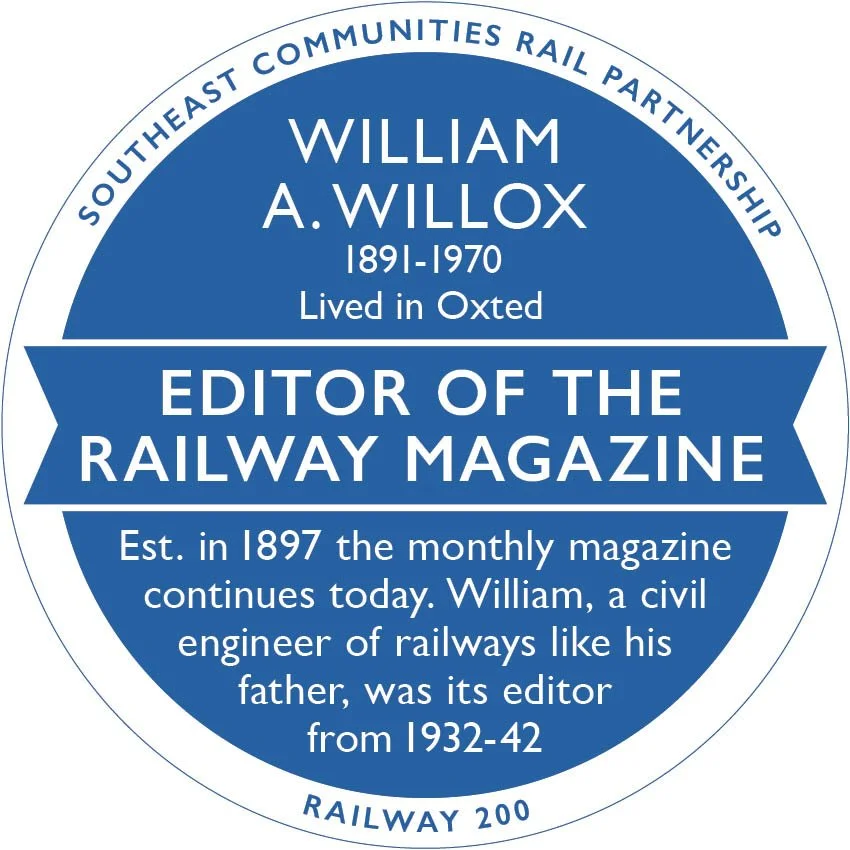

“Launched over 120 years ago by two former railwaymen suspecting a market amongst fellow rail enthusiasts The Railway Magazine features illustrated articles covering specific locomotives and carriages to major railway lines, junctions, tramways and light railways and how they function. The son of a railway engineer, William was its third editor”

-

Launched in 1897 by two former railwaymen suspecting a market amongst fellow rail enthusiasts. The Railway Magazine was well illustrated on good paper. The first editor George Nokes grew the circulation to 25,000, until 1910 when he fell out with the founders and started a rival magazine of his own. Both were bought by the Railway Gazette and then amalgamated into The Railway Magazine.

Articles covering specific locomotives and carriages to major railway lines, junctions, tramways and light railways and how they function, to unique railway uses such as Brookwood cemetery railway, milk trains and Queen Victoria’s funeral. New technologies such as electrification and signalling, and reminiscences about steam and lost lines.

William Willox was its third editor from 1932-42. Born in Scotland in 1892 to Elizabeth and William Snr. “a popular railway maker” who was chief engineer of the Metropolitan line for example, and whose work took him and his family abroad for periods of time since two of their daughters were born in the Philippines.

By 1901 the family were in Croydon, in 1911 they were in Dorset, where William Jnr was a civil engineering student. In 1921 William was in a guest house on Station Road in Oxted where he was based as a civil engineer for the LB&SC railway. Still in Oxted when he took on editorship of the magazine in 1932, in 1939 he was living with the Watsons, an architect and his wife on West Hill.

31-40

NORTH DOWNS LINE

Community Rail Line Officer - Sara Grisewood

“In 1909 Charlie was one of the first suffragettes on hunger strike to be forcibly fed. Despite or because of her arrest record for direct action and civil disobience David Lloyd George, then Minister for Munitions, employed Charlie during WWI as his mechanic and chauffeur”

-

Born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1887, to Ellen and Arthur Hardwick Marsh, a reknowned watercolourist, Charlotte Augusta Leopoldine Marsh had four sisters and two half-sisters. She was sent to Bordeaux finishing school and had training as a sanitary inspector.

Aged 20, she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, a campaign group - founded by Emmeline Pankhurst, engaging in direct action and civil disobience - for a woman’s right to vote in UK public elections. Charlotte became a full-time organiser, and would hand out Votes for Women leaflets and parade with placards. However in 1909 she was one of three women arrested for throwing tiles from the roof of Bingley Hall, Birmingham onto Prime Minister Asquith’s car below, in protest of being refused entry to a political meeting. The three were the first suffragette hunger strikers to be forcibly fed, Charlotte a reported 139 times, before her release. She was awarded a Hunger Strike Medal ‘for valour’ by the WSPU.

In the 1911 census, aged just 23, Charlotte was living on Portsmouth, and described as ‘Organising Secretary, Womens Suffrage League’. This was at a time when many suffragists boycotted the census - in fact, written across her census return the enumerator has written “This person... absolutely refuses to fill up paper”. Working from home at 43 Howard Road, Dorking (where there’s a blue plaque in her honour in 1912 Charlotte organised the suffragette campaign and travelled up and down to London by train.

During the First World War when David Lloyd George, the next Prime Minister, was still Minister for Munitions, he employed her as his mechanic and chauffeur. a political gesture, knowing the country relied on women to fulfil mens’ roles during a war.

Charlotte wasn’t wealthy and relied on trains to campaign, attend marches and meetings. Even special trains were laid on for large marches. Occasionally though trains and stations themselves were targets of fires or explosions, such as Oxted station and a train at Teddington, both occuring in the days following Mrs. Pankurst’s conviction for incitement (and 3 year prison sentence) in April 1913, were allegedly the work of militant suffragists.

In the Representation of the People Act of 1918, women (over the age of 30 who met certain criteria at least) were finally given the right to vote. This age limit was brought down to 21 to equal men in 1928, and 18 for all in 1969.

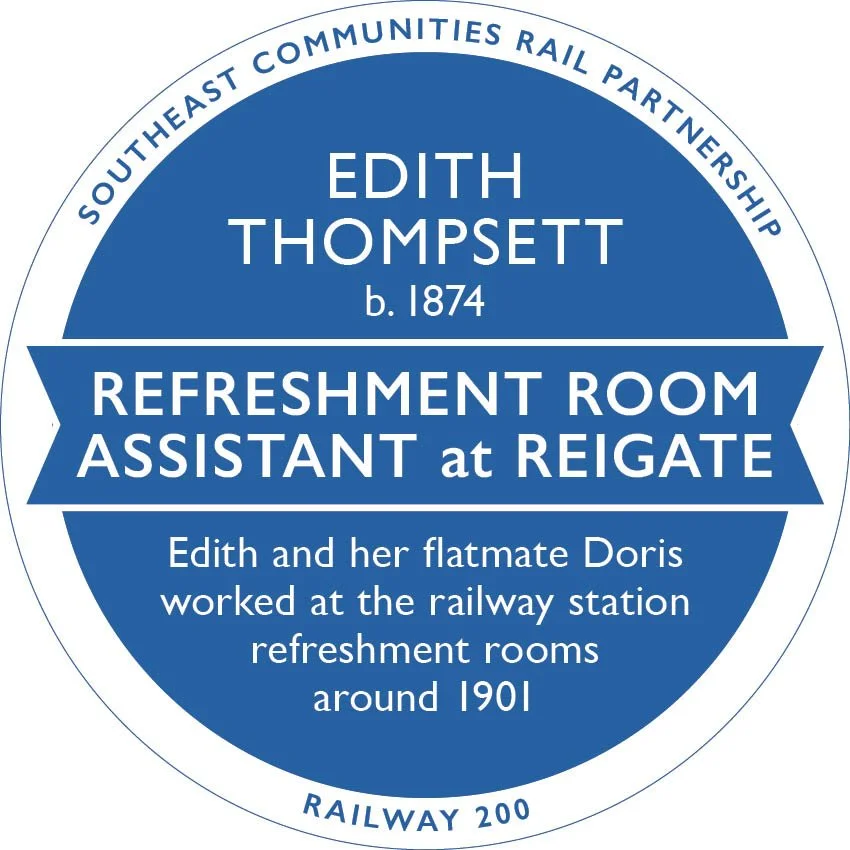

“Edith’s parents had the King’s Arms pub on Seaside Road, Eastbourne and in 1891 she was a barmaid in a Brighton hotel on Queens Road (now Princes House)”

-

Edith’s parents Albert and Henrietta Thompsett had the King’s Arms pub on Seaside Road, Eastbourne. An impressive Victorian building, large enough to house mum and dad, Edith, her six sisters, two brothers and a domestic servant.

Edith was born around 1874 and growing up around the serving of food and drink stood her in good stead. In 1891 she was a barmaid in a Brighton hotel on Queens Road, now Princes House. A decade on Edith and her colleague Doris Jupe were lodging on Clarendon Road, Reigate with the family of railway porter James Titchener. Edith and Doris were working at the refreshment rooms at Reigate station. Unfortunately Edith’s data trail disappears here. She likely marries before the next census, or perhaps boycotts the 1911 census (as Charlotte Marsh did).

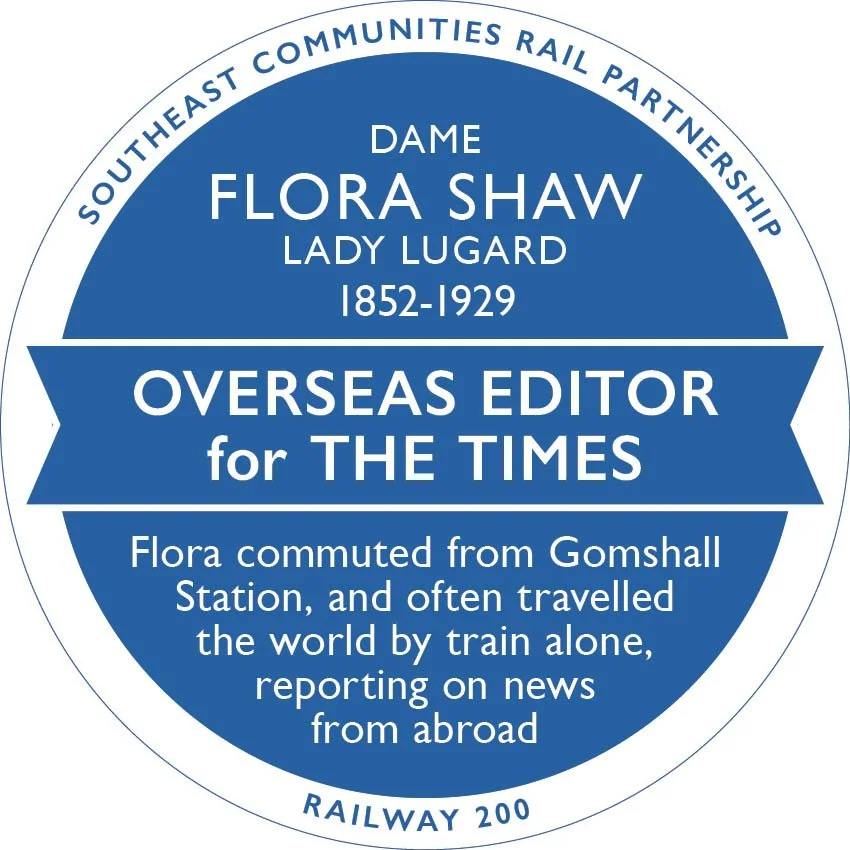

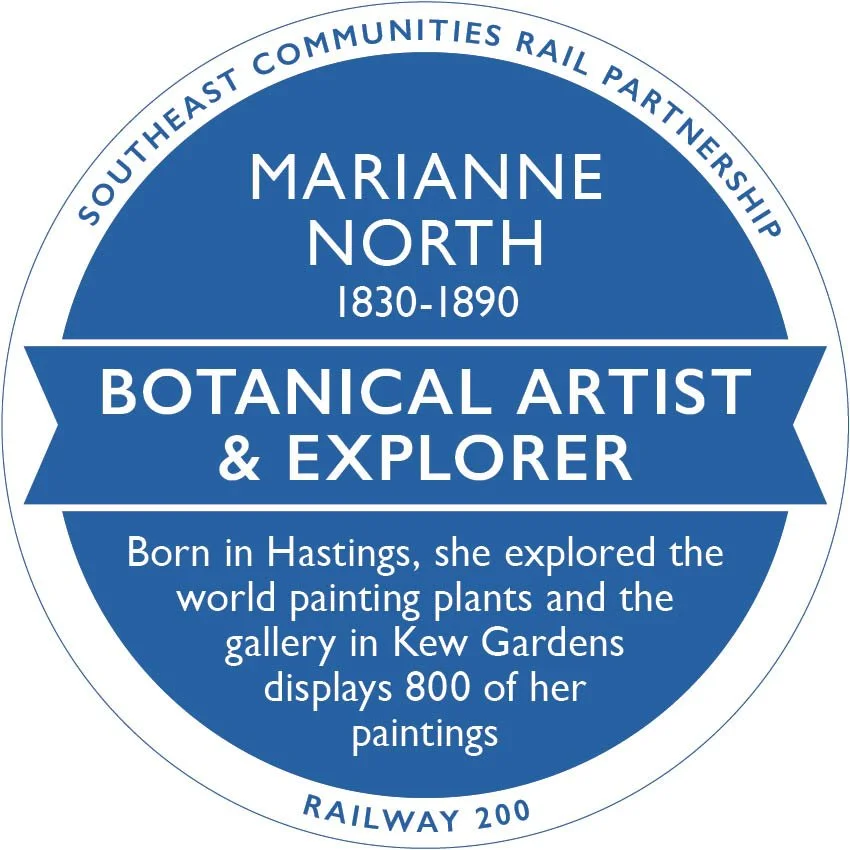

“On a six-day train journey across Canada she described it as ‘a land of clover and roses, the continuity of which is only interrupted by noble waterways and by mountain ranges of magnificent proportions’ and on a train in Australia, her ‘dress caught fire in the blistering heat’”

-

Born in Woolwich, one of 14 children of a Royal Artillery Capt. and his French wife. Flora wrote five novels for children and worked as a journalist.

She was the first female section editor of The Times, Colonial editor 1893-1900, which made her the highest paid female journalist at the time. She travelled daily up to London from Gomshall Station, in the 1890s from her home at Abinger Hammer. In an article for The Times in 1897 she suggested ‘Nigeria’ would be a better, shorter name for ‘Royal Niger Company Territories’.

In 1902 she married Frederick Lugard, and accompanied him in his role as Governer to Hong Kong and Nigeria. She also spent time in the British Colonies such as South Africa, Australia and even the gold fields of the American Klondike – exploring much of it by train - often describing her journeys in personal letters: For example, a six-day train journey across Canada was ‘a land of clover and roses, [...] the continuity of which is only interrupted by noble waterways and by mountain ranges of magnificent proportions.’ She recounted a tale to her sister, Lulu, of how on a train in Queensland, Australia, her dress caught fire in the blistering heat and was only put out by her male companion grabbing the outer layer of her dress in his hands to extinguish it, burning his hands in the process.”

Her enthusiasm for empire as an opportunity for emigration and investment, is distasteful to us nowadays. But she was clearly a strong minded woman, perhaps with an English untouchable arrogance of the day, often travelling alone on railways, often built on English expertise - and investment.

“Lily died at 31. For the funeral, her mother, three brothers, three sisters, uncles, aunts, cousins, all came over from Wales. Lily’s 18 year old sister Elsie stayed, and took on her late sister’s gatekeeping duties”

-

One of the youngest of at least eight children, Lily Florence Goodwin was born to William and Alice in 1918 in Stanleytown, Pontypridd in Wales. Her father and two working age brothers were coal miners.

Lily found her way to Surrey and in 1939 married railway permanentway labourer Frederick Percy. They lived at 234 Worplesdon Road, Guildford before moving to the cottage near East Shalford railway crossing where Lily took on the gatekeeping. It appears they had a son in 1944 they named Royston. Tragically Lily died of a congenital cerebral aneurysm* on 29 July 1949. She was 31.

For the funeral, her mother, three brothers, three sisters, uncles, aunts, cousins, all came over from Wales. Lily’s 18 year old sister Elsie stayed on, and took on gatekeeping duties.

“The orphanage was built on land bought from the London Necropolis Company. Naturally there was school work to do but there were toys to play with - such as a model railway - days out, useful skills to learn such as wood turning and shoe repair, and even a Scout group to join. Mothers could visit once a month”

-

Maintained by railworkers’ voluntary contributions, the orphanage began life in Clapham in 1885 as a home for children up to age 14, whose fathers had died building or working on the railways. It was a very dangerous occupation in those days - and a child’s mother might not be in a position to support them. In 1909 the orphanage moved to larger premises in Woking, built on land they bought from the London Necropolis Company, whose own railway or ‘ghost train’ had been carrying London’s dead from Waterloo to Brookwood Cemetery (in First and Second class carriages!) since 1854.

Born in Bury, Lancashire in 1874 to Susannah and John Core, a paper mill stoker. Her siblings were cotton spinners or weavers but Maria was to spend her working life in service. She was the domestic servant of a Baptist Minister a few streets away from home but by 1901 had moved away, working as a laundress at an Industrial school in Chelmsford. By 1909 Maria was in Woking, as Matron of the new Orphanage.

By 1921 her team of female staff included Rosina Love, assistant Matron; Florence Ashford was Head needle mistress; Janet Brooks was girls’ attendant and various kitchen assistants, domestic servants. The gardener was a man. At the time it was called ‘London & South Western Railway Servants’ Orphanage’ and was home to 120 children, many from Hampshire and Surrey but some from Ireland and Wales too.

Naturally there was school work to do but there were toys to play with - such as a model railway - and there were days out, useful skills to learn, such as wood turning and shoe repair, and there was even a Scout group to join. Mothers could visit once a month.

In 1934, after 25 years service Maria retired aged 60 and Grace Groom took over her role. Maria went to live with Mr and Mrs Bond at Heathercourt, Broomhall Lane in Woking. She died in 1945, aged 71.

“With military and civilian transport dependent on the railways, station master was a very responsible job and not one that would have been entrusted to a woman before 1914”

-

Edith Sheppard’s life and opportunities changed completely because of the war. She was able to take up a job that had only been open to men before.

Edith was born in Eastbourne in 1891 and had a brother Horace. Their father Sidney had been the stationmaster at Littleworth and later Ockley. During the war there was a shortage of railway staff as men enlisted or were conscripted. Some stations, like Box Hill Station, closed for lack of staff.

At Ardingly in West Sussex Edith became one of the first women stationmasters. She then moved to Dorking to become the stationmaster there. With military and civilian transport dependent on the railways, it was a very responsible job and not one that would have been entrusted to a woman before 1914. After the war many women returned to traditional roles, but they had changed people’s ideas about what women could do.

In 1915 her brother Horace, was killed riding his bicycle when it collided with a lorry under the South East & Chatham Railway bridge in Brockley, London. He was 19.

In 1921 Edith married Ardingly timber merchant Cyril Turner and they lived in Dorking and off Ardingly High Street, where she died in 1963.

Source: Kathy Atherton, Dorking Museum

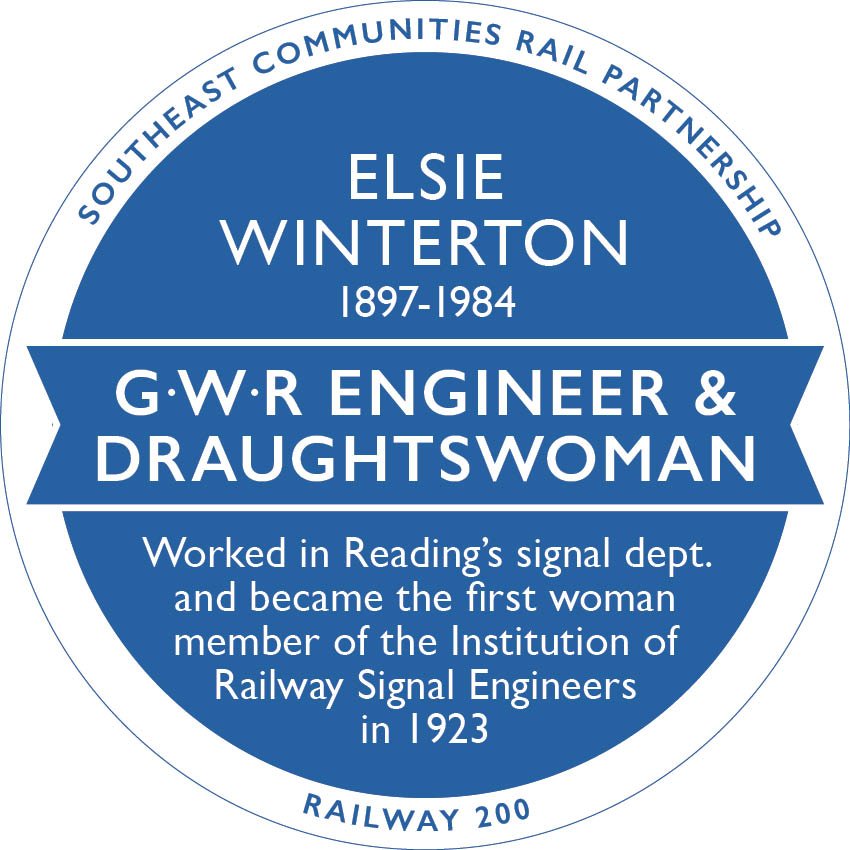

“At 24 Elsie was working as a tracer and draughtswoman in the GWR Signal Department in Reading, for example creating wiring diagrams of electronic railway signalling appliances”

-

Born in Reading in 1897, Elsie was one of nine children born to Rose and Joseph Winterton, a biscuit factory labourer for Huntley & Palmer. They were living at 112 Cumberland Road, Reading in the 1901, 1911 and 1921 censuses.

At 24 Elsie was working as a tracer and draughtswoman in the GWR Signal Department in Reading, for example creating wiring diagrams of electronic railway signalling appliances.

She became the first woman member of the UK’s Institution of Railway Signal Engineers (IRSE) in 1923” and “through her work at GWR and involvement with the IRSE, she met her husband, Edward Charles Deacon, and they were married in Caversham in 1930. As was usual at the time, she gave up her job to run the marital home but when her husband died in 1939, leaving her with two young children to support Elsie, Mrs. Deacon, rejoined the GWR Signal Department as a draughtswoman until her retirement in 1962, aged 65.

Elsie’s sister Ella Winterton passed the entrance exam and joined GWR in 1916 and also had a long career as a draughtswoman in Reading and later in Paddington. Another sister Doris joined GWR in 1929 and worked at Paddington station as a tracer’

“On Monday 29 February 1892 an express goods train carrying bricks, biscuits, corn, drainpipes etc, suffered an uncoupling as it descended the slope towards Chilworth. 35 of its 51 wagons derailed and many tumbled over the embankment, the guard’s van “was smashed to atoms” killing Henry the train guard”

-

Daughter-in-law of Henry Wicks. Jessie campaigned for a topiary tree in memory of Henry the railway guard killed by a goods train derailment near Chilworth in 1892.

Henry was born in Reading in 1839. By the time of his marriage in 1862 he was a railway guard. His bride was Emma Withers and they had three children Henry, Martha and Joseph. Living at 26 Cumberland Road in Reading.

On Monday 29 February 1892 a SER express goods train carrying bricks, biscuits, corn, drainpipes etc, suffered an uncoupling as it descended the slope towards Chilworth. 35 of its 51 wagons derailed and many tumbled over the embankment. According to the Berkshire Chronicle, the guard’s van “was smashed to atoms” killing Henry the guard on that train. The same paper reported that Henry “had been in the service of SER Company for upwards of thirty years... It was’t his turn to be on duty that night, he had voluntarily taken the place of another guard, who had gone to see his parents.”

His widow Emma stayed in the same house for some years before moving in with daughter Martha’s family and lived to the age of 88. Son Joseph, a gas and water engineer, married Jessie Williams in 1895 and moved to High Wycombe, they had a son Hubert.

It was Jessie who was instrumental in having the yew tree planted by the railway line, at the site of Henry’s death, as a memorial to her father-in-law. Clipped into the shape of a pheasant atop an armchair it’s known as ‘Jessie’s Seat’ or affectionately by some as ‘the Chilworth Chicken.’

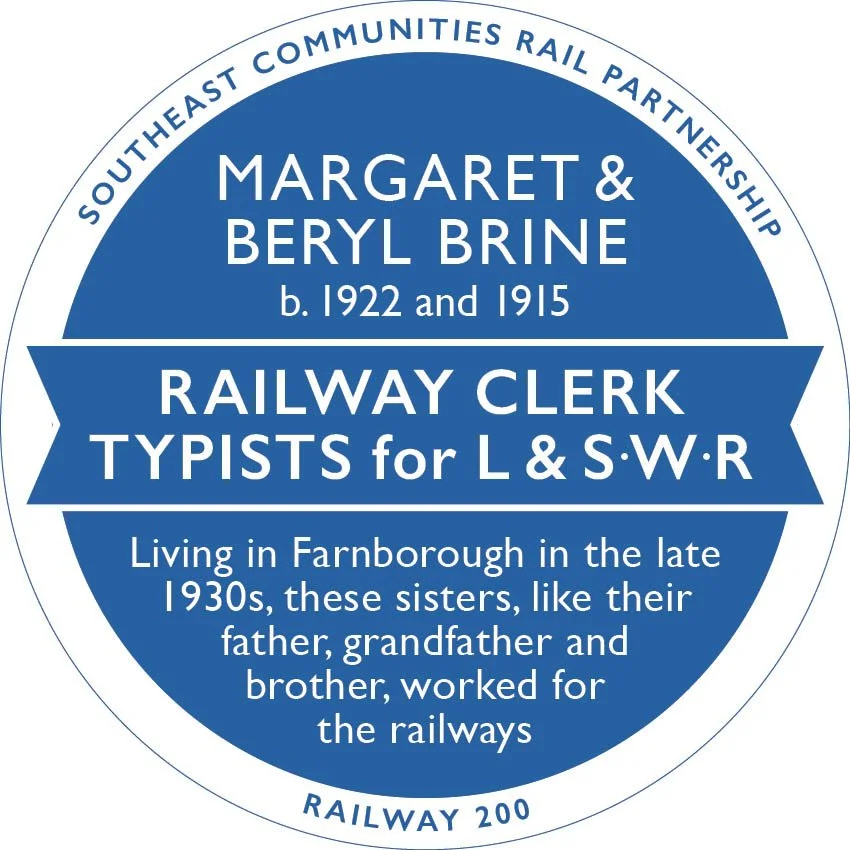

“Beryl bucked the railway trend and married a young farmer who had travelled to Canada a couple of times, on one occasion to the Agricultural Training School in Alberta. In 1946 Beryl took their two sons on the 14 day voyage to visit their father out there”

-

Margaret and Beryl’s paternal grandfather was a railway porter in Kingston-upon-Thames, and his son, their father Henry was at various times a railway messenger, an outdoor porter and goods clerk. Even their uncle Albert Brine was a railway parcels clerk, so a railway occupation would be hard to avoid.

The family were living in Cove by 1921, Beryl was 6, and she had two brothers, and Margaret arrived in 1922. In the 1939 identity card register both sisters were working as railway clerk typists and their father and brother were clerks too.

Margaret married railway clerk William Saitch, and had two children Janet and David. Beryl bucked the railway trend and married a young farmer, Liverpool-born Bernard Murtha, who had travelled to Canada a couple of times, on one occasion to the Agricultural Training School in Alberta, in the centre of Canada. In fact a couple of years after their marriage in 1946 Beryl took their two sons Bernard Jnr. and baby Peter on a 14 day voyage (each way) presumably to visit their father out there. The whole family did return to Surrey. Beryl and Bernard died just a year apart in 1981 and 82.

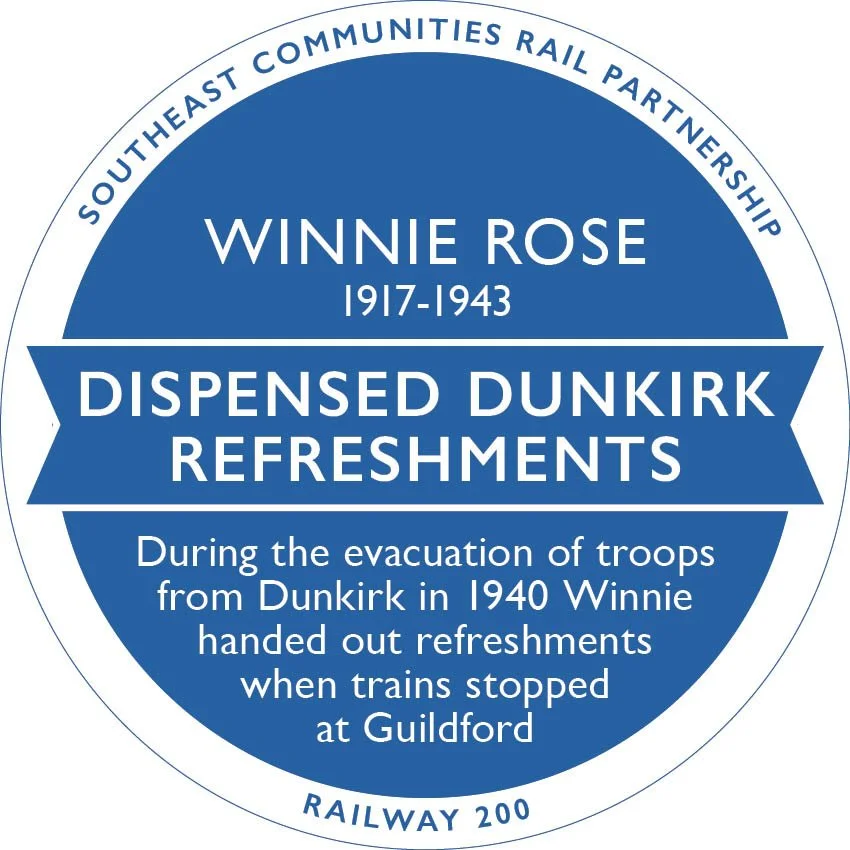

“She was among the volunteers who handed out food, drinks and cigarettes to the weary troops leaning out of their railway carriage windows and doors having been rescued from Dunkirk.

Tragically Winnie died in childbirth, aged 25”

-

Winnie was working in the buffet at Guildford railway station in May 1940 when trains conveying troops during the Dunkirk evacuation during the Second World War, stopped there.

She was among the volunteers who handed out food, drinks and cigarettes to the weary troops who were leaning out of their carriage windows and doors.

Known as Winnie, she was born in 1917, lived with her parents, sister and brother at 7 Falcon Road, Guildford. In 1939 she was doing laundry work and served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), at Hove in East Sussex, travelling exclusively by rail between there and home in Guildford.

In 1940 she married local boy Ronald Cranham, a builder’s labourer. Tragically she died aged 25 while giving birth to her son Ronald Jnr. who sadly didn’t survive either.

41-50

TONBRIDGE TO REIGATE LINE

Community Rail Line Officer - Sharon Gray

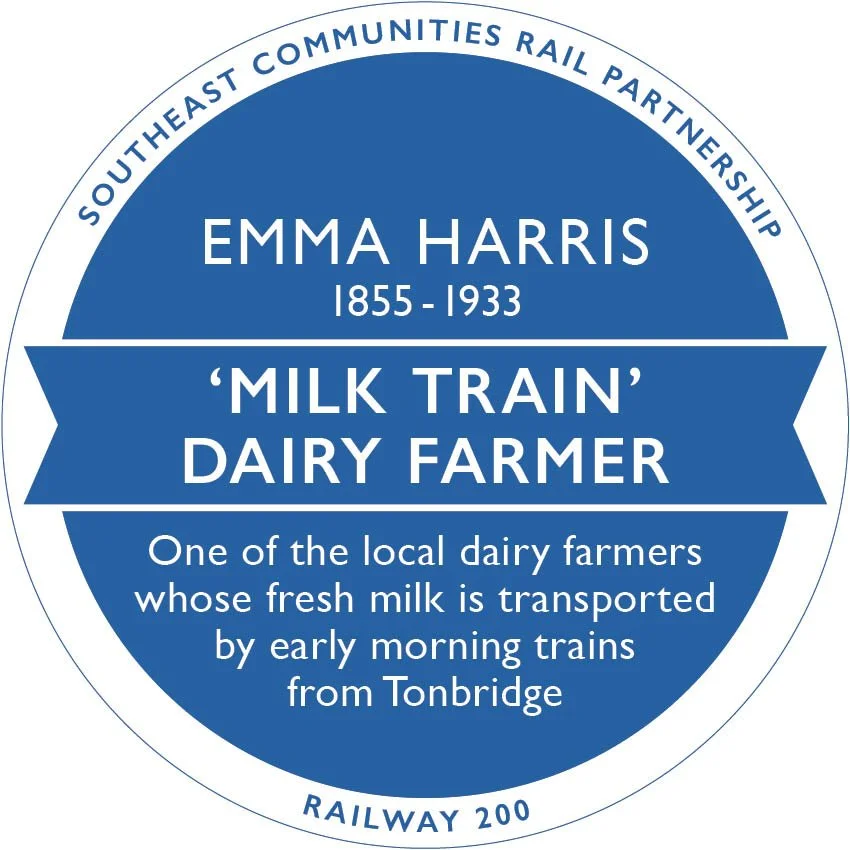

“In the 1920s milk from Emma’s dairy herds were being transported on morning trains from Tonbridge, 17 gallons (136 pints) of it daily. Nationwide some 282 million gallons of milk was being moved by rail in 1923”

-

The Roser family dairy farm was in Dry Hill, Tonbridge. It was run by Thomas and his third wife Hester.

Daughter Emma was born in 1855, one of four surviving children. When Thomas died in the 1870s Hester, now in her 60s, took on the farm herself - which in the 1880s totalled 70 acres, employing two men and three boys. They were living at 15 Shipbourne Road, Tonbridge (beside the George & Dragon pub).

A solicitor’s clerk called Ernest Harris - the son of a grocer on Tonbridge High Street - was lodging just a few doors away from the Rosers at No 4, and he and Emma were married. When Hester died in 1885, the farm’s value was to be divided equally between the children, so Emma and Ernest bought it themselves (which was contested in court!) By 1901 they had six children, who seem to have been given the middle name Roser. The sons became bank clerks and the youngest, daughter Ruby assisted her mother on the farm. In the 1920s milk from Emma’s dairy herds over in Ashurst were being transported on morning trains to Tonbridge, 17 gallons (136 pints) of it daily, and distributed by motor van.

According to one source 282 million gallons of milk was moved by rail in 1923, and this was gradually shifting to road.

Ernest died in 1924. Emma in 1933.

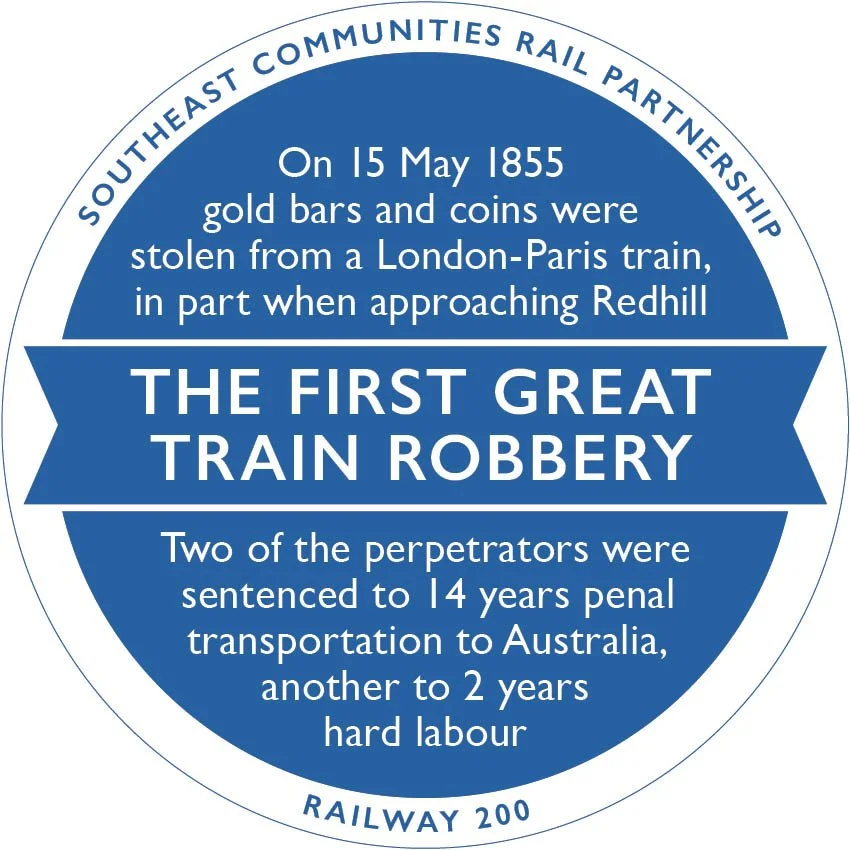

“The gold was said to be worth £12,000, just over £1m today in cash terms, but the value of gold itself has increased hugely from £4 an ounce to £2,400 an ounce since then, which might equate to over £7m today!”

-

On 15 May 1855 three locked, sealed and weighed consignments of gold bars and American coins - worth £12,000 - were sent in Chubb locked iron travelling safes by train from London to Paris. When they were opened it was discovered that bags of sporting shot had been substituted for the gold. A discrepancy in the weights of the safes along the route suggested it must have taken place on the South Eastern train somewhere between London and Folkestone. Hundreds of suspects were interviewed and many months of investigations passed yet the crime remained unsolved.

A man called Henry Agar had been convicted of cashing forged cheques in October 1855 and sentenced to be transported to Australia for life. From there he asked his friend William Pierce, who was holding a large sum on his behalf, to pass on some of that money to Miss Fanny Kay, a refreshment room attendant at Tonbridge railway station with whom he had a child. When it was clear William had kept the money for himself Fanny took her revenge. She reported her belief that Pierce was involved in the bullion robbery. Agar backed up Fanny’s claims with details of the crime. Implicating well-respected railwaymen James Burgess, guard of the van in which the safes travelled, and senior railway clerk William Tester, who arranged the roster of guards and knew the gold was on-board.

The travelling safes were provided by the railway company for such purposes, the keys being entrusted to the railway staff. After a fashion, wax impressions of the appropriate keys were made and counterfiet keys produced. When Tester knew a valuable gold consignment would be on board he assigned Burgess as guard and alerted Agar and Pierce to act. That evening, with first class tickets, Agar and Pierce boarded that train. They were in disguise and carrying heavy carpet bags (of lead shot) that the porter loaded into Burgess’s guard van. Under cover of darkness they moved into the guard van at a subsequent stop. The three men opened the safes, broke the wax seals and prised open the metal hooped boxes and switched the gold with approximately the same weight with lead shot from their bags. They replaced the metal hoops and created new wax seals. Tester was on board too, and at Redhill the first bags of gold were passed to him on the platform. Agar and Pierce bagged the remaining gold, tidied up, and changed carriages at a later station stop. At Folkestone they collected their carpet bags, spent the night in Dover and travelled back to London the next night where they met up with Tester. They melted down the gold in their backyard washhouse and a bedroom, forming small bars they could sell for gold sovereigns. These were exchanged at a bank for notes.

Agar, the self-appointed brains of the operation, was returned from Australia for the case to be tried at the Old Bailey in January 1857. He signed a confession and was kept in prison. Tester, who’d taken a railway job in Stockholm, was brought back to England where he, Burgess and Pierce all three pleaded not guilty. After all the evidence was heard the jury took just 10 minutes of deliberation to find them guilty of larceny. Burgess and Tester, being trusted railway employees, were given 14 years transportation for breaking that trust and Pierce, the lesser sentence of two years hard labour.

Having contracted tuberculosis Fanny took herself off to Hastings to recuperate, leaving her and Agar’s son Edward, and a trust fund, in the care of Pierce’s wife. But she died in Hastings in 1858, aged 27.

The gold was said to be worth £12,000, just over £1m today in cash terms, but the value of gold itself has increased hugely from £4 an ounce to £2,400 an ounce since then, which might equate to over £7m today!

Read historian Lorraine Sencicle’s encyclopedic account of the Great Bullion Robbery (in two parts) doverhistorian.com/great-bullion-robbery-part-i/

“Gunpowder was a moistened mixture of saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur and it’s rumoured that Guy Fawkes’ explosives came from an unauthorised maker in Battle. When the Leigh powdermill closed the Cheeseman family upped sticks to the Lake District, where Fanny’s husband became foreman of a gunpowder works there”

-

It’s rumoured that Guy Fawkes’ explosives came from an unauthorised maker in Battle. It wasn’t until the late 1600s that official powdermaking licenses were issued, the first to what is now Powdermill Lane, near Battle, with Tunbridge (as it was spelt then) following in 1813, in conjunction with Humphrey Davy and the Children family. Ingredients were a moistened mixture of saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur. This was then ground or ‘milled’ between large round, flat stones rather like a flour mill, powered by water, then compressed under heavy weights before processing into fine grained powder.

Inevitably accidental explosions occurred on site, killing workers, so it was a dangerous place to work. The powder was put into barrels and transported by road and river barges. In 1847 the GWR for example, concerned about moving explosives by rail (with the risks that steam engine sparks and fire posed) ordered that special ‘machines’ be used for transporting ‘gunpowder and combustible materials’ .